Free Guide To Critical Illness, Intensive Care, And Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

As a result of the current global health crisis, many more people than usual are having serious medical experiences. These include admissions to hospital with breathing difficulties, or transfers to critical care (intensive care) units. A significant proportion of these people will go on to develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

We wanted to put together a guide to give information to these patients, and to those close to them. It discusses how they might be feeling, why serious medical experiences can cause these difficult reactions, and the most effective psychological treatments.

This guide is for:

- People who have survived a frightening medical experience, such as being admitted to critical care (intensive care).

- People who have been hospitalized with severe medical problems related to COVID-19.

- Their family and friends.

- Mental health and medical professionals who want to understand more about how to help.

The guide gives information about:

- How you might feel after spending time in intensive care.

- Psychoeducation about PTSD.

- Things about intensive care that can contribute to the development of PTSD.

- Information about delirium.

- Psychological approaches to treating PTSD.

- Signposting to evidence-based treatment.

- Information for mental health professionals working with patients who have PTSD following admission to intensive care.

Our aim is for this to reach as many people who could find it useful as possible. We would love you to share it as widely as you can. With your support, the guide could be seen by many more people who could benefit from it.

Wishing you well,

Dr Matthew Whalley & Dr Hardeep Kaur

Download (UK English): Critical Illness, Intensive Care, And Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Download (US English): Critical Illness, Intensive Care, And Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Download (Albanian): Sëmundjet kritike, Kujdesi intensiv dhe Çrregullimi i Stresit Pastraumatik (PTSD), (thanks to Nebahate Ejupi and Rrezarta Isma)

Download (Arabic): المرض الحاد, العناية المركزة, و اضطراب ما بعد الصدمة, (thanks to Marie Wilson [PWP Peterborough Psychology Team], and Shams Al-Nahar Basbous)

Download (French): Maladies Graves, Soins Intensifs, Et Syndrome de Stress Post-Traumatique, (thanks to Christine Lacroix and Virginia Rogers)

Download (Greek): Κρίσιμη Ασθένεια, Εντατική Θεραπεία και Διαταραχή Μετατραυματικού Στρες (ΔΜΣ), (thanks to Athina Papageorgiou and Panagiota Alvanou)

Download (Italian): Malattia critica, terapia intensiva e disturbo post-traumatico di stress (PTSD), (thanks to Aurora Cartwright-Madaffari and Elisabetta Cairo)

Download (Polish): Poważna choroba, Intensywna Terapia i Zespół Stresu Pourazowego (PTSD), (thanks to Paweł Kaliniecki and Sonia Izabella Barciuk)

Download (Romanian): Boli Critice, Terapie Intensivă și Tulburare de Stres Post-Traumatic (PTSD), (thanks to Popescu Ioana-Mirela)

Download (Russian): Тяжелые заболевания, интенсивная терапия и посттравматическое стрессовое расстройство (ПТСР), (thanks to Elena Karyakina)

Download (Spanish): Trastorno por Estrés Postraumático (TEPT) asociado a Enfermedades Críticas y Cuidados intensivos, (thanks to Alicia Cerrato Grande, Sara Rivera Molina, Joan González, Andrés Calvo Abaunza, Yaddira Molano Santiago, Israel Mallart Ortega, Brenda Morales Torres, Alejandra Morales Phipps, Carolina Haylock-Loor, Ahsley Gibbs, Elizabeth Eastman)

Download (Tagalog): Kritikal na Sakit, Masinsinang Pangangalaga at Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), (thanks to Roy B. Macaraig)

Download (Turkish): Kritik Hastalık, Yoğun Bakım ve Travma Sonrası Stres Bozukluğu (TSSB), (thanks to Gul Eryuksel)

Download (Vietnamese): Bệnh hiểm nghèo, Chăm sóc tích cực và Rối loạn căng thẳng sau sang chấn (PTSD), (thanks to Ho Huy Duc)

Can you help by translating part of this guide?

If you would like to help by translating this guide we have created Google Doc translation templates. If you click on the link you will be able to view & edit the document. Using Google Docs means that the translation effort can be shared amongst many people. If you’re having any technical issues, or need us to add templates in more languages just get in touch ([email protected]). Do make sure to add your name at the top of the document so that we can credit your contribution.

- Afrikaans

- Albanian

- Arabic (already complete)

- Bulgarian

- Chinese (Simplified)

- Chinese (Traditional)

- Croatian

- Czech

- Dutch

- Estonian

- Finnish

- French

- German

- Greek (already complete)

- Hebrew

- Hindi

- Hungarian

- Icelandic

- Italian (already complete)

- Japanese

- Korean

- Kurdish

- Latvian

- Lithuanian

- Malaysian

- Norwegian

- Polish

- Portuguese (European)

- Portuguese (Brazilian)

- Punjabi: contact us

- Romanian (already complete)

- Russian (already complete)

- Serbian

- Slovenian

- Somali: contact us

- Spanish (International) (already complete)

- Swedish

- Tagalog (already complete)

- Turkish

- Ukrainian

- Vietnamese (already complete)

- Welsh

Critical Illness, Intensive Care, And Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Welcome to this Psychology Tools guide to critical illness, intensive care, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Psychology Tools’ mission is twofold: to ensure that therapists worldwide have access to the high-quality evidence-based tools they need to conduct effective therapy, and to be a reliable source of psychological self-help for the public. We have made this guide freely available because, as a result of the current global health crisis, many more people than usual are having serious medical experiences. These include admissions to hospital with breathing difficulties, or transfers to critical care (intensive care) units. A significant proportion of these people will go on to develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

This guide is for:

- People who have survived a frightening medical experience, such as being admitted to critical care (intensive care).

- People who have been hospitalised with severe medical problems related to COVID-19.

- Their family and friends.

- Mental health and medical professionals who want to understand more about how to help.

If you have had any of the experiences described in this guide, you might find some of the examples ‘triggering’ or upsetting. Remember that there is nothing in this guide which can harm you, and that learning about what has happened (and is still happening) to you can help your recovery. We suggest that you read it slowly in sections, and that if you find it too overwhelming to approach it with the help of a health professional.

How do people feel after being treated in an intensive care unit?

Being critically ill is a physically and emotionally overwhelming experience. Naturally, given the scale of what you have been through, it takes time to recover. How you feel, and how long it takes to recover will depend on what type of illness you had, and how long you were unwell. Some very common experiences after discharge from an intensive care unit (ICU) include:

- Feeling physically weak. Even doing simple things like getting dressed, moving about, or getting out of the bath can take enormous effort.

- Fatigue. You might feel exhausted, and may feel the need to sleep more than normal.

- Numbness or other changes in how parts of your body feel.

- Feelings of breathlessness upon mild exertion, like walking up the stairs.

- Changes in your appearance which might include changes in how your hair, skin, or fingernails look and feel. You might also be recovering from surgical scars.

- Hoarse voice, especially if you had a breathing tube.

- Effects on how you feel mentally. You may feel more forgetful, or struggle to read more than a few sentences. It’s natural to feel like you have a ‘foggy’ brain and struggle to concentrate on anything or get anything done.

- Emotional changes including feeling irritable, depressed, or anxious. You might not feel like going out, or when you do you might feel overwhelmed in crowded places.

Overwhelming worries such as concern about getting ill again, or worrying you will never recover. You may worry what some of your critical care experiences mean for your mental health: for example worrying about hallucinations that you may have had when in hospital.

Recovery can take longer than you might expect. Symptoms such as muscle weakness are still very common even six months after discharge from hospital.

Researchers interviewed people who had been discharged from ICU [1].These are some of the things they said:

- “I get panicky if I go out alone in case I am taken ill”

- “I get very angry with my family. They keep fussing when I try to do things for myself ”

- “I feel very angry with myself for not being back to normal by now”

- “I’ve tried to help by doing the washing up but I keep dropping the crockery”

- “When I first went home I climbed the stairs on my hands and knees and came down on my bottom”

Does any of this sound familiar? These are all normal experiences to have after needing critical care in hospital. The body and mind take time to heal, and it is important to be patient with yourself while you recover.

What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

PTSD describes a collection of symptoms that some people have after their life was in danger, or where there was the possibility of suffering serious injury. You might also feel this way when you witness these kinds of things happening to a loved one – such as watching a loved one in intensive care. Traumatic events which can occur during admission to hospital can include:

- Moments where you believed that you were going to die.

- Frightening, invasive, or painful medical experiences.

- Moments when you received bad news, and had thoughts about what this meant for you, or for those you love.

- Hallucinations caused by medication, delirium or other illness.

- Experiences where you felt powerless, or where you felt that you weren’t being helped.

- Experiences where you were aware of other people dying.

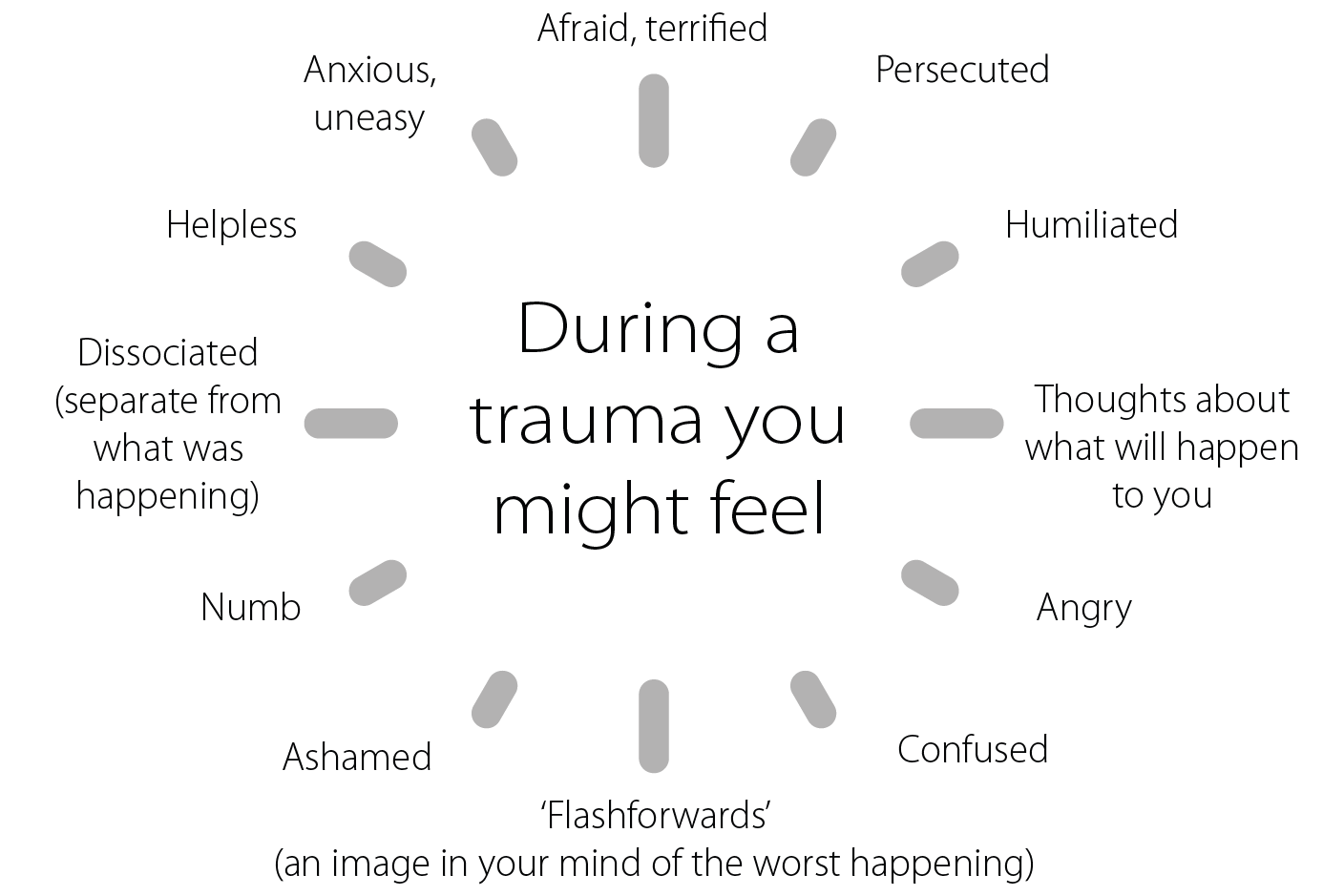

During a trauma it is common to feel powerful emotions and body sensations, or to have frightening thoughts. You might have had some (or none) of the following thoughts and feelings:

Figure: Common thoughts and feelings during traumatic events.

Once a traumatic experience is over, it can take some time to come to terms with what has happened. It is normal to feel shocked, overwhelmed, or numb for days, weeks, or even months afterwards. For most people these feelings subside with time, but for other people they persist and start to impact on your life.

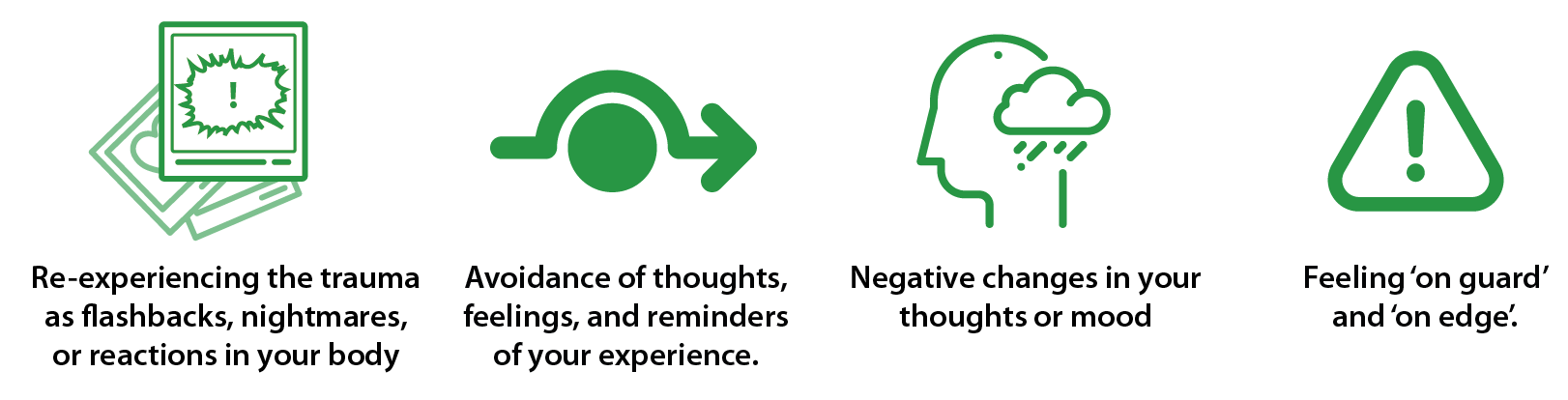

What are the symptoms of PTSD?

You might receive a diagnosis of PTSD if you experience these symptoms after a trauma:

- Re-experiencing the trauma as flashbacks, nightmares, or reactions in your body. You might experience unwanted memories of your trauma which can ‘pop’ involuntarily into your mind and are often accompanied by powerful emotions. Your memories might be triggered by reminders of your medical experience such as seeing a hospital drama on TV, or receiving notice of a medical appointment. You might experience:

- Factual memories (memories of events that really happened) such as remembering being told bad news.

- Memories of hallucinated events – hallucinations are very common in people who are severely ill. You might have seen or heard things that you later found out were not really there.

- Memories of things that you thought when you were ill. For example, patients in intensive care sometimes think they are being persecuted by medical staff who are actually trying to help them.

- You may experience a mixture of these symptoms.

- Avoidance of thoughts, feelings, and reminders of your experience. This might include avoidance of people or places, avoidance of reminders, or trying to avoid or suppress your own thoughts or memories. After a traumatic medical experience you might find medical appointments anxiety-provoking, you might try to avoid TV programs about hospitals, or you might even try to avoid looking at or touching parts of your own body that remind you of what happened.

- Negative changes in your thoughts or mood. For example, some people have frighten- ing hallucinations while they are ill and worry (incorrectly) later on that they might have a serious mental health problem. Others think they are being mistreated in hospital and these beliefs persist after they leave. After a critical illness many people become a lot more worried about getting ill again. Any of these beliefs can make you feel very anxious or depressed.

- Feeling ‘on guard’ and ‘on edge’. After a trauma it is common to feel anxious or unable to relax. Some people feel more angry or irritable than before. You might have difficulty with your sleep.

How common is PTSD?

It’s normal to experience some symptoms of PTSD after a trauma. Fortunately, for most people these start to get better in the first month. However, depending on the type of trauma 20-30% of people experience symptoms of PTSD that persist. After treatment in intensive care PTSD is experienced by about 1 in every 5 people.

Figure: After treatment in intensive care, PTSD is experienced by about 1 in every 5 people.

How does intensive care cause PTSD?

By definition, if you are admitted into an intensive care unit then you are at your most poorly. You require round-the-clock monitoring and invasive medical procedures to provide life support. Patients in intensive care are often connected to a wide range of machines: common ones include heart monitors and artificial ventilators (when patients can’t breathe for themselves). Many life support machines beep and make loud noises to alert staff to changes in the patient’s condition. Patients are also likely to be fitted with several tubes either putting fluid and nutrients in, or taking other fluids out. Most ICU patients are sedated, but not always completely unconscious. It is common for patients in ICU to have their arms or legs restrained in order to prevent them from removing tubes or equipment. All of these interventions are to help you survive the immediate crisis, however they can also be frightening.

Figure: Treatment in intensive care is invasive, and involves a lot of specialist equipment.

There are many of aspects of critical care medicine that can contribute to the later development of PTSD.

Do any of these remind you of your hospital experience? The main priority of the intensive care unit was to help you survive, and so everything that was done to you was done with that intention. However, you might be living with the unintended aftermath of post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Psychologists working with people who have been admitted to intensive care know that it is common for them to have unpleasant – and often unusual – experiences during their hospital admission. The following case reports are anonymized, but they describe experiences commonly reported by intensive care patients.

Tanya’s story

Tanya was thirty-five when she went into hospital for a planned operation on her lungs. The first surgery did not go as planned and while she was in the recovery ward she expe- rienced severe swelling throughout her entire body. She remembers her doctors looking concerned and saying that she needed a further operation. The second operation was not successful, and she spent more time in the recovery ward feeling extremely unwell (“the most ill I’ve ever been”) before going back into surgery for a third operation. She hazily remembered signing a consent form for the final surgery, and the next thing she was aware of was waking up somewhere strange.

Tanya was very ill, medicated, and delirious. She drifted in and out of consciousness. She experienced hallucinations in this state – she thought nurses were ninjas, and believed that she had been kidnapped and was being held captive on a boat. She felt terrified and persecuted. She felt like this went on for weeks.

The doctors had needed to place a central line into a large vein in her neck. She was intubated and mechanically ventilated so that a machine could breathe for her. With tubes in her mouth she could not talk or communicate. Tanya had flashes of memory of trying to reach up to feel what was uncomfortable near her neck, and someone trying to stop her. She later found out that it was a nurse trying to stop her from pulling the lines out, but at the time she felt helpless and tortured.

Tanya took a long time to recover physically. It was a year after her time in critical care when she began a course of psychological therapy. Tanya’s psychologist listened to her, and said that she was experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Tanya was reliving terrifying flashbacks from her hospital admission: some of these included flashbacks of the hallucinations she had experienced, and she would feel the same sense of helplessness when she had these unwanted memories. She was also profoundly distressed because she believed she was somehow bad, or to blame, because she had caused so much worry to her family: during a relatively lucid moment in hospital she described imagining her family suffering without her, and even imagined them being homeless and on the streets because she had died.

Tanya completed a form of psychological therapy called eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) where she was encouraged to think about and helped to ‘process’ what had happened to her. She and her therapist reviewed the ‘ICU diary’ that her intensive care nurse had put together for her, which helped her to place events in some order. During the therapy she pieced together important fragments of her memories which she had found so distressing and confusing. Approaching her trauma memories was frightening for Tanya – when she thought about them again she felt persecuted, just like she had in intensive care. With time though, she found that her sense of fear lifted and came to no longer believe that she was powerless. She started to make sense of what had happened and her flashbacks reduced. It was important for her to realize that nurses had been helping her, and that the ‘ninjas’ had been hallucinations.

One belief which Tanya struggled with in particular was her idea that she was bad because she had caused distress to her family. She remembered lying in her hospital bed and imagining them suffering without her, and would be overwhelmed by feelings of guilt. She worked with her therapist to express and resolve these feelings, and eventually came to realize that she was not responsible for how events had unfolded. She found it helpful to ‘update’ her catastrophic image of her family, with a happy of one of them all a year later. When she stopped blaming herself she felt more able to offer herself the kindness and patience that helped her physical recovery.

Dave’s story

Dave was sixty and suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and a heart condition. He was poorly after an operation, and he wasn’t recovering as he had expected to. He had been feeling breathless for a few days and when it began to worsen he went to see his family doctor. His doctor was so concerned about him that she tele- phoned for an ambulance which took him straight to the emergency department. In the emergency department Dave continued to feel very short of breath despite being given oxygen. He was moved to a respiratory ward and spent five hours being extremely short of breath – he described fighting for every breath.

Eventually his doctors decided that Dave needed to be transferred to intensive care. By this point he was exhausted and was sure that he would die. He was transported up to the intensive care unit but there was a delay as the elevator door was not working properly, and he remembered thinking he would die in the elevator. Dave subsequently spent four days in the intensive care unit. He was mechanically ventilated until his condition became stable enough for him to be moved back to the respiratory ward. Dave recovered enough to leave hospital after another week.

When he returned home Dave started having repeated nightmares and flashbacks of a coffin lid being put on him. He found these terrifying and would avoid going to sleep in an attempt not to have them: he would often spend all night on the couch in front of the television. The flashbacks brought up memories that Dave couldn’t make sense of, but which made him feel very anxious. He felt like he couldn’t cope, and he started to avoid things which bothered him such as lifts and hospitals.This was particularly problematic for Dave because he needed to attend regular hospital appointments for his COPD and heart condition. To make things worse, Dave’s employer was not supportive of his condition and he was experiencing pressure to keep working more than was healthy for him.

When he started psychological therapy many months later Dave initially reported not being aware of much of his stay in the intensive care unit. He knew from his wife that he had stayed for four days, had been mechanically ventilated, and had also been restrained.

He did not know much more, because his wife became so upset when he asked her about it. During therapy Dave learned that he was experiencing symptoms of PTSD. His therapist explained that his avoidance of things that reminded him of his experiences in hospital was understandable, but might be hindering his recovery.

In therapy his therapist asked him to replay his ICU memories slowly and carefully. Dave remembered an occasion in ICU when he was sure that he had died and a coffin lid had been put on him – he came to understand that the ‘nails’ were actually details in the ceiling above him that he had misinterpreted due to the delirium he was experiencing at the time. Later in therapy, an important part of Dave’s treatment involved revisiting the hospital where he had been treated. Accompanied by a nurse, he and his therapist re-traced Dave’s journey from the emergency room, to the respiratory ward, to the intensive care unit – including a trip in the elevator that had malfunctioned. He found it anxiety-provoking to confront his fears, but with encouragement he was able to expose himself to the things he was afraid of. He came away with the knowledge that he had survived. He started to go to his hospital appointments again, and gradually his fear reduced and he started to feel confident again. As he recovered, he recognized that his wife also had developed symptoms of PTSD, and he supported her to seek treatment.

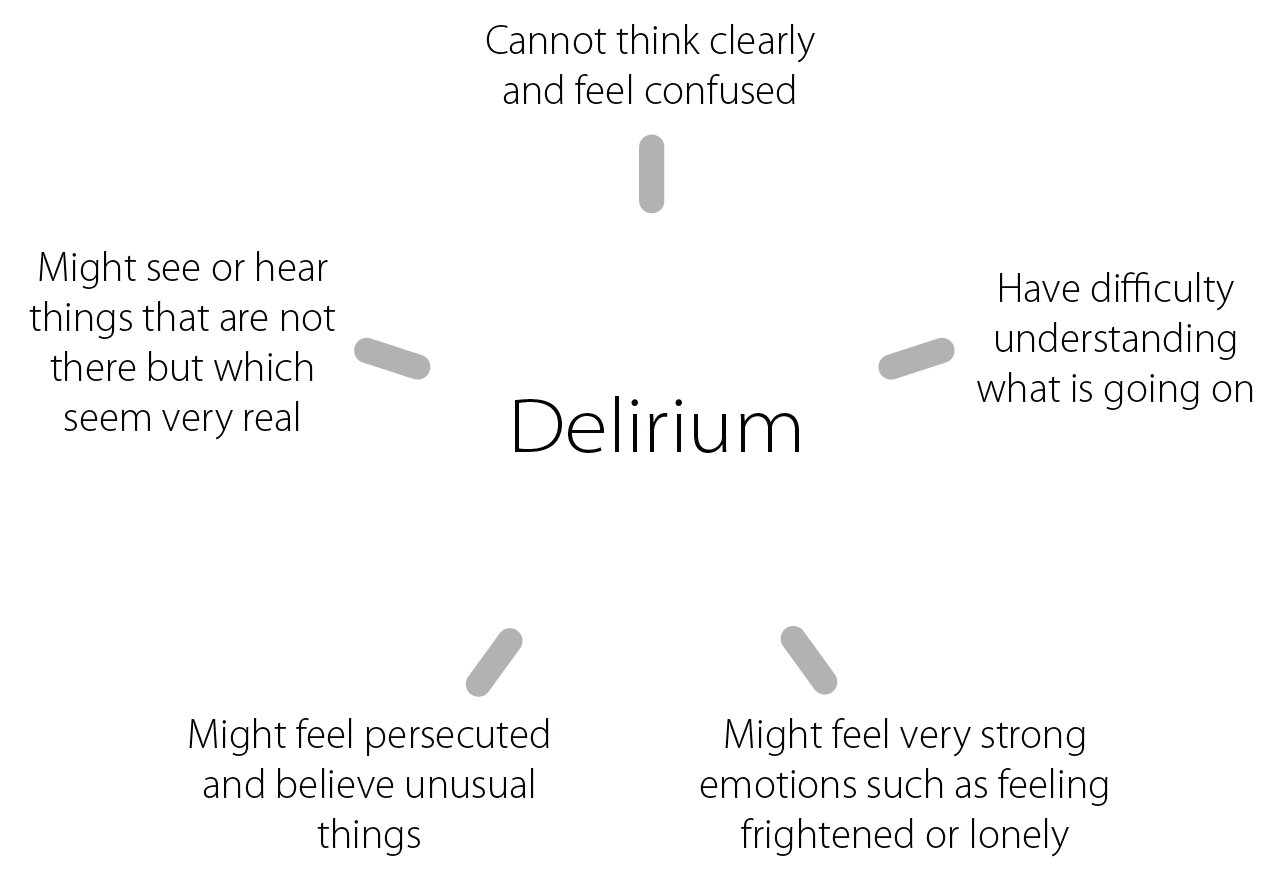

Delirium

Many patients who suffer a critical illness and require intensive care suffer from delirium. Delirium is a severe state of confusion.

Figure: Delirium is the medical name for a severe state of confusion.

If you experienced delirium during your hospital admission you might be worried about what it means. Some people worry that it is a sign that they are mentally ill or going crazy. Don’t worry – it doesn’t mean either of these things. Delirium is actually very common in medical settings. Between four and nine out of every ten patients in intensive care become delirious. This rises to eight out of ten patients who needed the support of breathing machines [3].

Doctors think that delirium is caused by changes in the way that the brain works. This can happen when:

- Your brain receives less oxygen.

- There are changes in how your brain uses oxygen, and when there are chemical changesin your brain.

- You are on certain medications, or under anaesthetic or sedation.

- You have a severe infection, or are suffering from certain medical illnesses.

- You are in severe pain.

- You have reduced eyesight or hearing.

- You are of older age.

If you had experiences of seeing or believing unusual things when you were in ICU the chances are high that it was the result of delirium. Fortunately, delirium is temporary and passes once the underlying cause is treated. If you are continuing to have experiences like the ones you had in hospital it is likely that these are PTSD flashbacks of the hallucina- tions that you had in hospital, and not a sign that the delirium is continuing.

Recovering from PTSD

Although PTSD is extremely distressing to suffer from, it is fortunately a very treatable condition. The first step in overcoming PTSD is to understand how it gets ‘stuck’ and why it doesn’t get better by itself. Psychologists have developed a very helpful way of thinking about PTSD which helps to put all the pieces together. So how does PTSD develop, and what keeps it going?

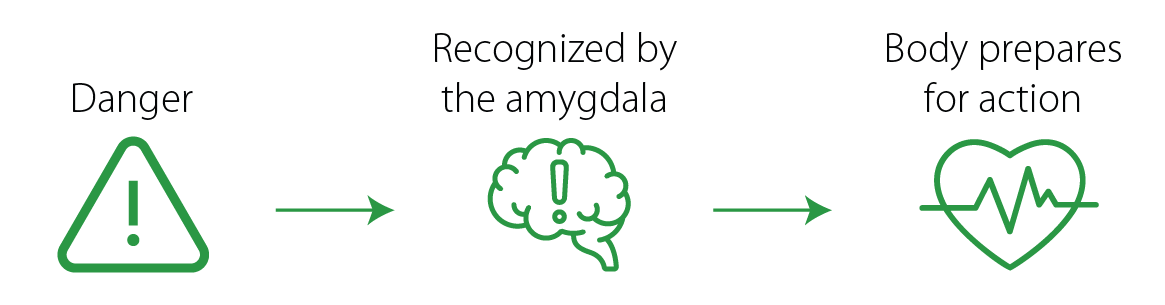

1. Your threat system is active and has stayed active

Your brain & body contains a ‘threat system’ or ‘fight or flight response‘ whose purpose is to help you to stay alive. One part of your brain – the amygdala – has the job of identifying dangers. It is triggered by anything that could threaten your life – and sets off an ‘alarm’ in your body to help you to get ready to respond. The motto of this threat system is ‘better safe than sorry’ – it would rather set off a false alarm nine times than miss one real danger.

Figure: Your threat system recognizes danger and prepares your body to respond. After a traumatic experience your threat system might be on high alert.

While your threat system is active you might find it difficult to sleep or relax, might feel ‘jumpy’, or alert to other dangers around you. After a traumatic experience, like admission to ICU, it is normal for your threat system to stay on high alert for some time afterward. For people who have PTSD it seems to take even longer to return to normal.

Your threat system can be triggered by imagined dangers as well as real ones. You might find that even thinking about what happened to you can trigger feelings of anxiety and tension.

Tanya was frightened during her time in hospital, and for a long time afterwards. When she described it to her psychologist she told him how frightened she had been knowing that the first two operations had not worked and that she needed another. She also described how terrified she felt when she was in intensive care and powerless when she thought that she was being held captive. After Tanya left hospital her anxiety just continued – her flash- backs were frightening and made her worry that she was going mad, she felt ‘on edge’, she found it difficult to sleep, and she didn’t like to be around other people.

2. PTSD memories are different

PTSD memories are different from normal memories. Some of the qualities that can make them particularly distressing are:

- Immediacy. When PTSD memories ‘play’ in your mind it can feel as though the event is happening right now in the present moment. You might even lose track of where you are.

- Vivid. PTSD memories are often so vivid that they seem real. You might hear sounds or smell smells that your experienced during your traumatic event with such clarity that you feel you are back there again.

- Involuntary. PTSD memories feel less ‘under control’. They can pop into your mind unexpectedly, and can be difficult to suppress.

- Fragmented. You might only remember parts of what happened, or your memory might keep replaying the worst parts.

It is not your fault if you experience memories like these. Your memories are this way because of your neurobiology – the way that your brain is designed. Psychologists think that trauma memories like these are stored differently by the brain. An important task during trauma therapy is to ‘process’ memories so that they are not so distressing.

During her time in ICU Tanya was delirious and thought that she had been kidnapped by people who were planning to do her harm. When she was discharged from hospital Tanya had many unwanted memories of things that she had experienced in ICU. She had memories of conversations she thought she had overheard, and she felt the same feelings of terror that she had felt at the time. When these memories ‘played’ in her mind it felt like she was back in the ICU. They were so strong that she could smell things again – the smell of cleaning chemicals – and she could hear the beeps of machines. When she re-experienced these odd memories it made her doubt what was real and what wasn’t.

3: PTSD is all about meaning-making

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) works with our thoughts and beliefs, because it un- derstands that they are what drives our feelings. What makes PTSD so distressing, and part of what keeps it going, are the ways that you have made sense of what has happened to you. Sometimes our interpretations are completely accurate, but other times they may be unhelpfully off-the-mark.

While she was in intensive care Tanya was very ill and had to be restrained to stop her from pulling out her tubes. Her delirium meant that she hallucinated that the nurses were ninjas. The meaning that Tanya’s (delirious) brain made of this experience at the time was that she was being held captive and persecuted – and she felt frightened as a result. After she was discharged from hospital Tanya had nightmares and flashbacks which replayed this trauma. These felt so real and her interpretation of these experiences was that she was going mad – which made her feel even more frightened.

| Event | Interpretation | Feeling |

| Being in ICU and realizing that I couldn’t move | I’m being held captive | Frightened |

| Nightmares of ninja nurses | I’m going mad | Frightened |

Table: How Tanya interpreted some of her experiences during and after her time in ICU.

Unhelpful interpretations of events can keep you ‘stuck’. Psychological treatments for PTSD involve updating any unhelpful meanings of your trauma.

| Unhelpful Meanings | Helpful Meanings |

| I’m being held captive by masked ninjas. | I was being cared for in hospital by masked nurses. |

| I’m going to die, my life is in danger. | My life was in danger, but I’m safe and recovering now. |

| Nobody is listening to me, nobody cares about me. | I couldn’t speak because I had a tube in my wind- pipe. I was being cared for then, and people care about me now. |

| I’m going mad, it’s not normal to have experiences like these. | I was delirious in ICU and I experienced hallucinations. This is very common and it doesn’t mean that I am going mad. |

| Maybe I’m not safe to be looking after my children now. | I’m not going mad, I am recovering from PTSD and am capable of looking after my children safely. |

Table: Some of Tanya’s unhelpful meanings, and the more helpful perspectives that she discovered.

4: Sometimes the things we do to cope are counter-productive

All of us try our best to cope with how we are feeling. One problem in PTSD is that the things we do to cope sometimes turn out to be unhelpful. Do you use any of the coping strategies below?

| Coping Strategy | Intended Effect | Unintended Effect |

| Avoiding reminders. | Avoid distress. Feel better. | Memory of the trauma remains ‘unprocessed’. Life is restricted by anxiety. |

| Not talking about it. | Avoid distress. Don’t want people to think I’m mad. |

Memory of the trauma remains ‘unprocessed’. Don’t get reassurance from loved ones or professionals. I keep thinking I’m mad. |

| Using alcohol or drugs. | Sleep better. Control how I am feeling. |

Sleep gets worse Don’t feel better. Addiction / dependence |

| Avoid thinking about what hap- pened, keep suppressing it. | Avoid feeling distressed. | Suppressing things leads them to ‘bounce back’ and experience them more strongly. |

| Checking / scanning for symptoms. | Detect symptoms before they become serious. | Keep having ‘false alarms’ and noticing unimportant symptoms. |

Table: Coping strategies have intended and unintended consequences.

5. Putting it all together

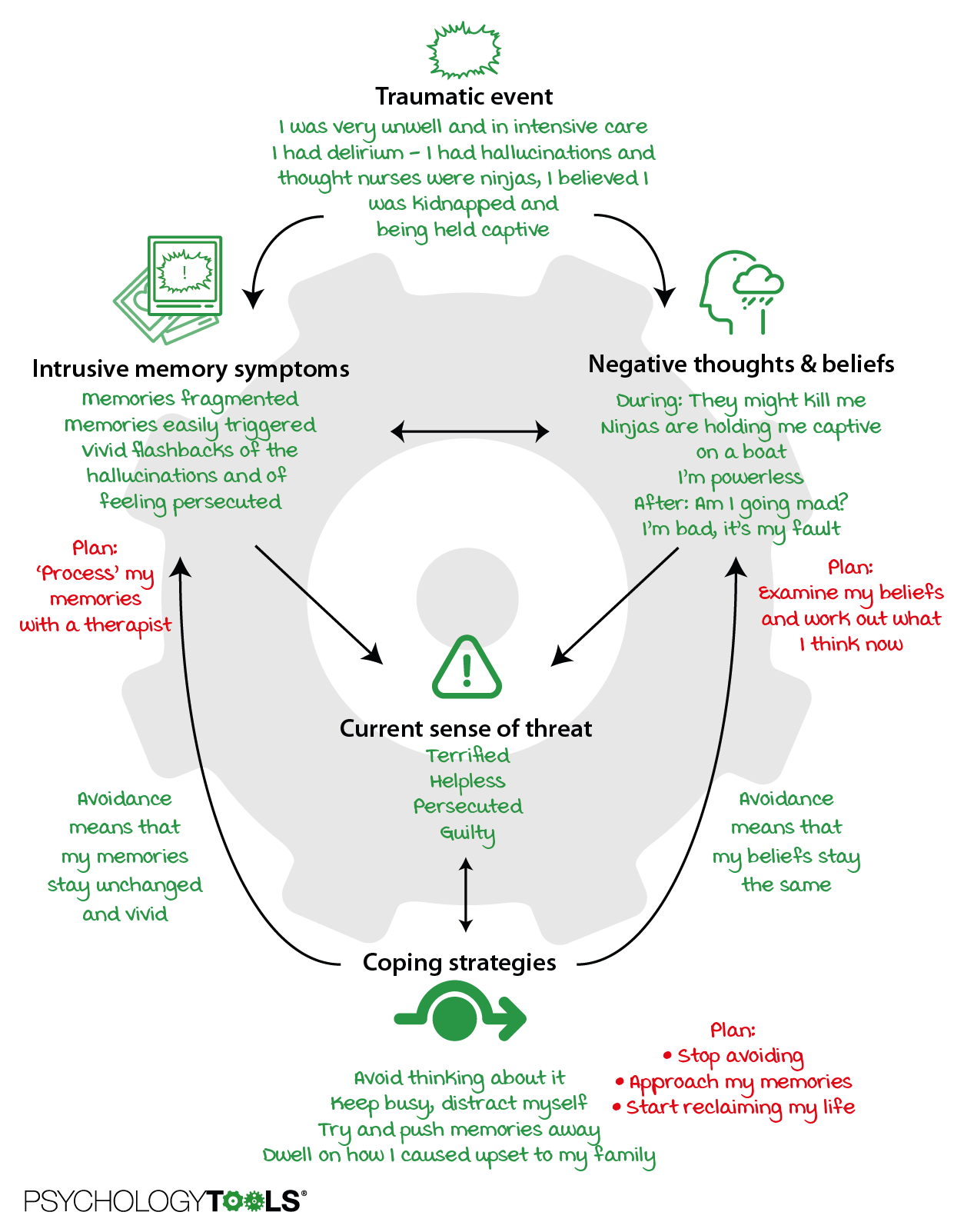

If we put all of these steps together you start to understand why PTSD doesn’t get better by itself. This is the ‘vicious cycle’ that Tanya’s therapist drew with her. Tanya found it helpful because it made sense of what was going on for her. And it gave them a plan for what they needed to do in treatment.

Psychological treatments for PTSD

There are excellent evidence-based psychological treatments for PTSD. Some of the most well-researched are:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapies (CBT) including Cognitive Therapy for PTSD (CT-PTSD) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Although these treatments might differ in some of their specifics, what they all involve is: - Some exposure to your trauma memory. PTSD memories can be a bit jumbled (intensive care memories even more so). Talking about and writing about what happened to you can help to ‘process’ these memories and make them less intrusive and distressing

- Meaning-making. Making sense of what happened to you, understanding the sense that you made of these experiences at the time, and helping you to re-evaluate these ideas in the light of what you know now.

- Learning different coping strategies. Overcoming avoidance, learning healthier ways of coping, and reclaiming your life.

Special therapy tasks if you have been in intensive care

Some components of treatment that can be particularly helpful for people who have ex- perienced ICU include:

- Learning about the ways that physical illness, delirium, and things about the medical environment that can affect you psychologically.

- Leaning about hallucinations and flashbacks, and why they happen. It is important that you understand that just because you experienced hallucinations during ICU, or flashbacks afterwards, does not mean that you are going mad or are in any danger.

- Reading medical records to find out what happened to you day-by-day (to fill in gaps in your memory). If your trauma went on for a long time psychologists will often help you to make a ‘timeline’ to piece together your story.

- Site visits if they are possible. Revisiting the ICU (or looking at pictures or videos) can help to ‘process’ your trauma memories and to correct any unhelpful beliefs. Many people find it helpful to meet the staff who cared for them.

- Understanding that you might have strong ‘body memories’ of what happened to you. These might be experienced as flashbacks, or you might re-experience them during trauma treatment.

- Accepting that there might be gaps in your memory because you were not conscious for the entire time.

What should I do if I think I might have PTSD after a critical illness?

Step 1: Screening

If you think that you might have PTSD then a good first step is to complete this short questionnaire. You can’t diagnose yourself with PTSD, but it can indicate whether you might benefit from a full assessment by a mental health professional.

Sometimes things happen to people that are unusually or especially frightening, horrible, or traumatic. For example being admitted to a critical care (intensive care) unit. Have you ever experienced this kind of event? YES / NO

If yes, please answer the questions below.

In the past month, have you:

1. Had nightmares about the event(s) or thought about the event(s) when you did not want to?

YES / NO

2. Tried hard not to think about the event(s) or went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of the event(s)?

YES / NO

3. Been constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled?

YES / NO

4. Felt numb or detached from people, activities, or your surroundings?

YES / NO

5. Felt guilty or unable to stop blaming yourself or others for the event(s) or any problems the event(s) may have caused?

YES / NO

If you answered YES to three or more of these questions then you might be suffering from post- traumatic stress disorder. You might wish to contact a mental health specialist for a full assessment.

Step 2: Speak to a professional

If you think you are experiencing symptoms of PTSD you might like to seek help from a professional. You should contact your family doctor, or a psychological therapist.

To find a therapist trained in CBT

- USA:http://www.abct.org

- UK:https://www.babcp.com

- Europe:https://eabct.eu/about-eabct/member-associations/

- Australia:https://www.aacbt.org.au

- Canada:https://cacbt.ca/en/

To find a therapist trained in EMDR

- USA:https://emdria.org

- UK:https://emdrassociation.org.uk

- Europe:https://emdr-europe.org/associations/european-national-associations/

- Australia:https://emdraa.org

- Canada:https://emdrcanada.org

Information for mental health professionals working with patients who have PTSD following admission to intensive care

Even therapists who are used to working with survivors of trauma can be ‘thrown’by certain aspects of ICU trauma. Fundamentally, psychological treatments for ICU trauma use the same elements as when treating other types of trauma. However, therapists might find it helpful to be familiar with the details below, and to seek appropriate supervision when working with this population. If you have experienced medical trauma and are planning to seek therapy you might find it helpful to discuss this page with your therapist.

Trauma memories: duration, fragmentation, content

Stays in intensive care may range from days to weeks. The duration of the stay can mean that patients have experienced a higher ‘dose’ of trauma than some other trauma survivors and that there may subsequently be more trauma memories to work with.

Patients are unlikely to have been conscious for the entirety of their stay in the ICU. They are likely to have had impaired consciousness, memory encoding is likely to have been affected, and retrieval will be subsequently impacted. It is to be expected that patients will have gaps in their memory and these can be acknowledged. During memory processing you can use the prompt “And what is the next thing that you can remember?”.

Therapists should expect that trauma memories of critical care experiences will be partic- ularly fragmented, and may contain a mixture of ‘real’ and ‘hallucinated’ content. It is often helpful to construct a timeline of the person’s hospital experiences which incorporates information from their memory, medical records, and ICU diary if one is available, as well as descriptions from family and friends. Constructing an illustrated or written narrative is often helpful.

Experiences of delusions or hallucinations in ICU may appear to persist post-discharge

Delirium is extremely common in patients who have required intensive care, and can cause hallucinations and delusional beliefs. If these experiences appear to be persisting post-ICU it may be helpful to conceptualize them as involuntary memories of their expe- riences of active attempts at meaning-making, which were encoded during physiological states of delirium.

To give a clinical example. ‘Mark’ was ventilated and sedated during his ICU stay, and he experienced delirium. One of his nurses was of Asian origin and during this time he perceived that he was being persecuted by Asian gangsters. After he had physically recovered he still felt afraid around people of Asian appearance, experienced unwanted memories of Asian faces, and held the belief (somewhat less strongly than during his time in ICU) that he was being watched by a gang of Asian men. The conceptualization that he found most helpful was that his threat system was easily triggered by similarities to his trauma memory (Asian faces), and his unwanted memories were flashbacks of his time in ICU. Both of these reduced in intensity with therapeutic exposure to his trauma memories. He subsequently conducted some behavioral experiments to test his beliefs about being watched and re-evaluated his belief to the less-threatening “nobody is paying me particular attention”. Once his memories had been ‘processed’ and his beliefs re-evalu- ated he no longer felt such distress by his memories of ICU.

Patients may describe particularly strong ‘body memories’ or feelings during trauma memory reprocessing

Patients might describe these experiences spontaneously during assessment or memory processing, but might also find it helpful if the therapist sensitively enquires about such experiences directly. For example, patients might report unpleasant sensations in their throat related to the experience of intubation, or discomfort in their groin related to catheterization. As with regular trauma memories of visual or auditory experiences, memory reprocessing of (i.e. exposure to) these somatosensory memories is an effective form of treatment. If patients spent time in ICU lying down on their back, or in a prone position, it may be helpful to conduct some parts of memory work in therapy with the patient in a similar body position.

‘Pain flashbacks’ are a real phenomena and are worth exploring

Flashbacks are forms of involuntary memory. They are often experienced in visual and auditory modalities, but olfactory (smell) and somatosensory (touch) memories are also commonly reported. Research indicates that individuals who experience physical pain during their trauma can re-experience this pain in the form of flashbacks, but that many will not spontaneously report these experiences. Clinical experience indicates that these memories can be processed in the same way as other traumatic memories.

Appraisals of trauma consequences need to be addressed

Appraisals following critical care experiences might touch on a number of important domains, and can be addressed using cognitive and behavioral interventions. For more information clinicians are directed to Murray et al (2020) [4] which discuss clinical approaches to some of these in more detail.

- Beliefs about mental illness or mental integrity due to experiences of delirium. Beliefs might include themes such as “I’m going mad”, “I can’t trust my own mind”, or “I’m not in control”. Patients might feel ashamed of the way they behaved during their treatment.

- Beliefs about loss. These might include beliefs concerning loss of physical function, or losses of a previous way of living.

- Beliefs about body image. These might include beliefs about permanent change such as “I’ll never be the same again”, or other beliefs about scars or other body image changes such as “I’m disgusting”.

- Health concerns. It is common for patients who have had serious medical experiences to fear recurrence of their illness, or other illness which could result in readmission to hospital. Such health anxiety may also generalize to concern for loved ones.

- Beliefs concerning medical treatment and healthcare staff. Feeling angry about aspects of medical treatment is not uncommon, and some patients may feel mistrustful of healthcare staff.

Site visits and records access

Helpfully, patients may be able to access records of their admission to intensive care, detailing the time course of their illness and the medical procedures they underwent. Some hospitals will create a patient-friendly ‘ICU diary’ and such information is often useful in therapy when helping patients to untangle their experiences.

In some circumstances site visits to intensive care are possible and many patients report these to be helpful. In-vivo site visits are presently unlikely due to coronavirus, and so virtual site visits are a viable alternative.

Therapists should help clients to look for information which will help them to understand where hallucinations might have originated, or which might help them to update beliefs. For example our client ‘Dave’ came to understand the ‘coffin nails’ he saw in ICU were likely to have been details in the ceiling. When ‘Tanya’ visited ICU she saw how gently the nurses interacted with patients, and how softly they encouraged them not to interfere with tubes, and came away with updated information “they are trying to help not harm”.

Patients may report ongoing triggers

Triggers might be visual, such as medical staff, locations, or physical staff. Triggers can also be auditory, such as beeping machines. They might also be somatosensory including lying in particular positions. Patients can be encouraged to use stimulus discrimination to discriminate between ‘then’ and ‘now’, both to naturally occurring triggers experienced in their daily life, as well as to deliberate provocations in the therapy room.

References & further reading

[1] Griffiths, R. D., & Jones, C. (1999). Recovery from intensive care. BMJ, 319(7207), 427-429.

[2] Righy, C., Rosa, R.G., da Silva, R.T.A., Kochhann, R., Migliavaca, C. B., Robinson, C. C., Teche, S. P., Teixeira, C., Bozza, F. A., Falavigna, M. (2019). Prevalence of post-trau- matic stress disorder symptoms in adult critical care survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care, 23, 213.

[3] Cavallazzi, R., Saad, M., & Marik, P. E. (2012). Delirium in the ICU: an overview. Annals of Intensive Care, 2(1), 49.

[4] Murray, H., Grey, N., Wild, J., Warnock-Parkes, E., Kerr, A., Clark, D. M., Ehlers, (2020). Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder following critical illness and intensive care unit admission. Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, (April 2020).