Guide (PDF)

A psychoeducational guide. Typically containing elements of skills development.

An accessible and informative guide to understanding obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), written specifically for clients.

A psychoeducational guide. Typically containing elements of skills development.

To use this feature you must be signed in to an active account on the Advanced or Complete plans.

Our ‘Understanding…’ series is a collection of psychoeducation guides for common mental health conditions. Friendly and explanatory, they are comprehensive sources of information for your clients. Concepts are explained in an easily digestible way, with plenty of case examples and accessible diagrams. Understanding Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is designed to help clients suffering from OCD understand more about their condition.

This guide aims to help clients learn more about obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). It explains what OCD is, what the common symptoms are, and effective ways to address it, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Designed to help clients understand and learn more about OCD.

Identify clients who may be experiencing obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

Provide the guide to clients who could benefit from it.

Use the content to inform clients about OCD and help normalize their experiences.

Discuss the client’s personal experience with OCD.

Plan treatment with the client or direct them to other sources of help and support.

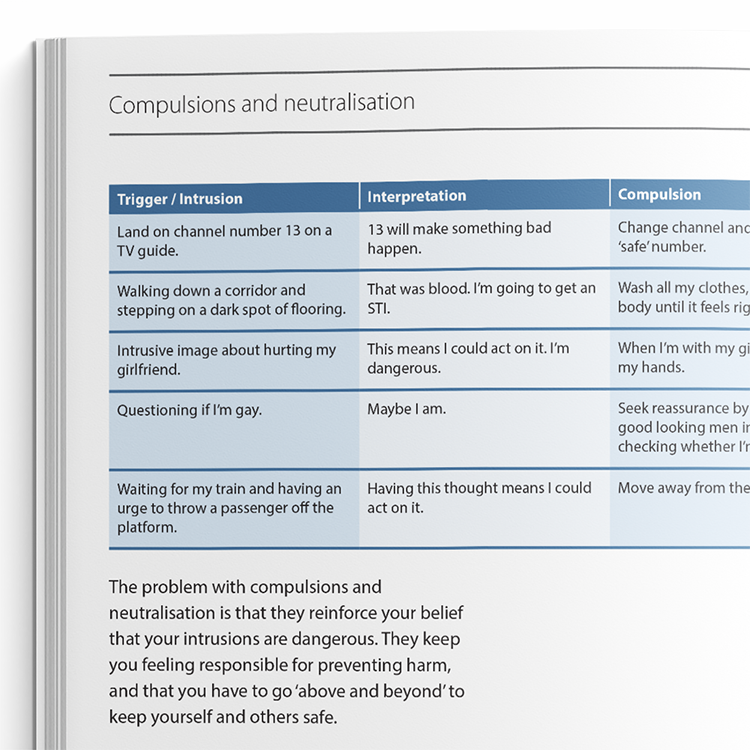

Obsessions are intrusive, unwanted thoughts or mental images that clients typically experience as distressing, unacceptable, or anxiety-provoking. In response to these obsessions, clients may engage in compulsions - repetitive behaviours or mental acts intended to prevent feared outcomes or to alleviate emotional distress. When obsessions and compulsions reach a level that significantly disrupts daily functioning, the individual may meet criteria for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Prevalence estimates suggest that OCD affects approximately 1–2% of the population annually.

The Understanding Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) guide has been developed to support clients in building a clearer understanding of OCD. In addition to outlining common symptoms and evidence-based psychological treatments, the guide also introduces core psychological processes that are believed to maintain OCD symptoms. These include safety strategies, neutralizing actions, and attention and reasoning biases.

Just enter your name and email address, and we'll send you Understanding Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) (English US) straight to your inbox. You'll also receive occasional product update emails wth evidence-based tools, clinical resources, and the latest psychological research.

Working...

This site uses strictly necessary cookies to function. We do not use cookies for analytics, marketing, or tracking purposes. By clicking “OK”, you agree to the use of these essential cookies. Read our Cookie Policy