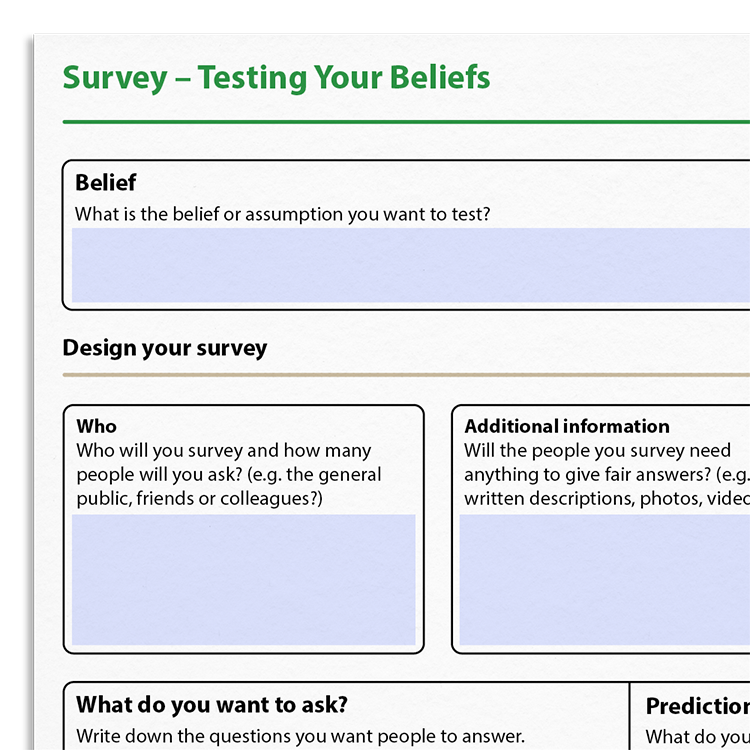

Professional version

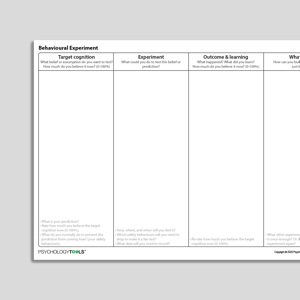

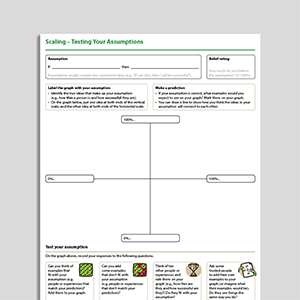

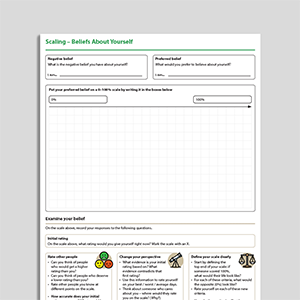

Offers theory, guidance, and prompts for mental health professionals. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.

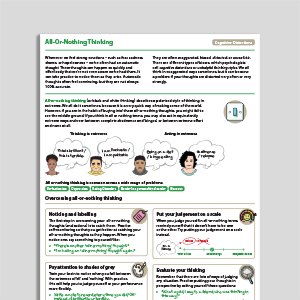

Client version

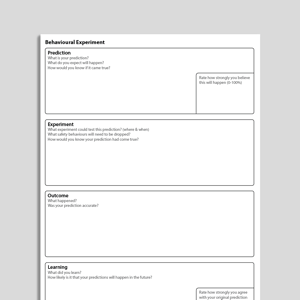

Includes client-friendly guidance. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.