Professional version

Offers theory, guidance, and prompts for mental health professionals. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.

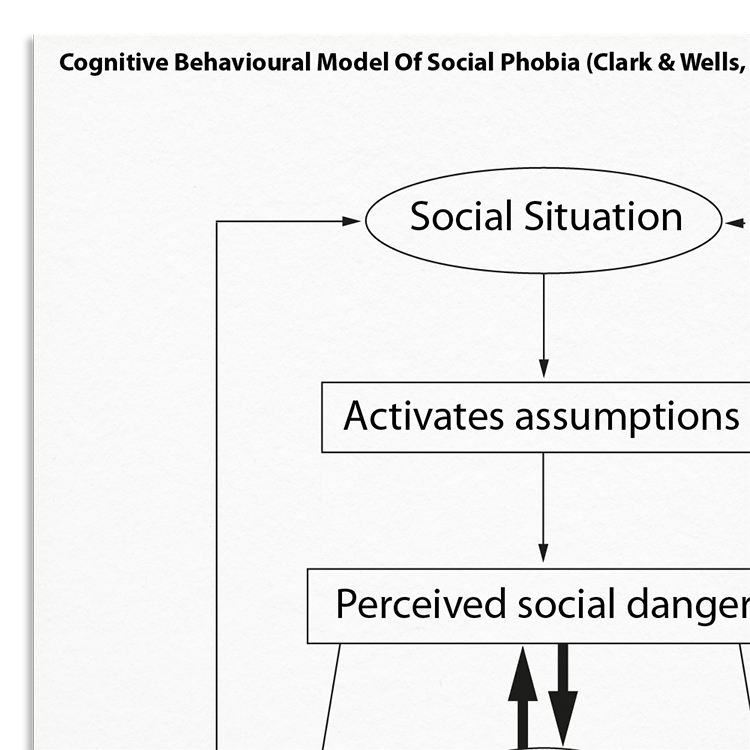

A licensed copy of Clark and Wells (1995) cognitive behavioral model of social phobia (also known as social anxiety disorder).

Offers theory, guidance, and prompts for mental health professionals. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.

People suffering from social anxiety disorder (SAD; previously known as social phobia) experience persistent fear or anxiety concerning social or performance situations that is out of proportion to the actual threat posed by the situation or context. They fear negative evaluation and worry excessively about social events and outcomes, both before social situations and afterwards. Common fears include speaking or acting in ways that they think will be embarrassing or humiliating, such as shaking, sweating, blushing, freezing, appearing stupid or incompetent, or looking anxious. They fear that other people will judge them negatively, for example that they appear anxious, stupid, crazy, boring, dirty, or unlikable. They therefore make efforts to ensure that their fears do not materialize, resulting in clinically significant distress and impairment, often across multiple domains of their life. This information handout describes the original Clark and Wells (1995) cognitive model of social phobia.

Understanding the underpinnings of social anxiety is important for effective intervention.

Ideal for clinicians working with individuals affected by SAD.

Understand more about the cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety.

Use the model as a template to organize your case formulations.

Use your knowledge of the model to explain maintenance processes to clients.

Engage clients in discussions about their beliefs and behaviors.

Customize interventions based on individual maintenance mechanisms.

Use in supervision to discuss case conceptualizations and treatment plans.

Individuals suffering from social anxiety disorder (previously known as social phobia) experience persistent fear or anxiety concerning social or performance situations that is out of proportion to the actual threat posed by the situation or context. Situations that can provoke anxiety include talking in groups, meeting people, going to school or work, going shopping, eating or drinking in public, or public performances such as public speaking.

Clark and Wells’ model of social phobia, published in 1995, provides a cognitive behavioral formulation of social anxiety. Clark (2001) describes how the model attempts to solve the ‘puzzle’ of why social anxiety persists despite regular exposure to feared social situations.

The model proposes that entering a feared situation activates a set of beliefs and assumptions that have been shaped by one’s earlier experiences. These beliefs and assumptions concern both the individual, and how they think they should behave in social situations. Holding these assumptions predisposes socially anxious individuals to appraise particular social situations as dangerous, and to make predictions that they will not meet their own (often high) standards for performance.

Once a situation has been appraised in this manner, Clark and Wells propose that an ‘anxiety program’ is activated automatically. This program leads to automatic changes in affective, attentional, behavioral, cognitive, and somatic processing which are intended to protect the individual from harm, but which are accompanied by unintended consequences that serve to maintain the social anxiety.

Just enter your name and email address, and we'll send you Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Social Phobia (Clark, Wells, 1995) (English US) straight to your inbox. You'll also receive occasional product update emails wth evidence-based tools, clinical resources, and the latest psychological research.

Working...

This site uses strictly necessary cookies to function. We do not use cookies for analytics, marketing, or tracking purposes. By clicking “OK”, you agree to the use of these essential cookies. Read our Cookie Policy