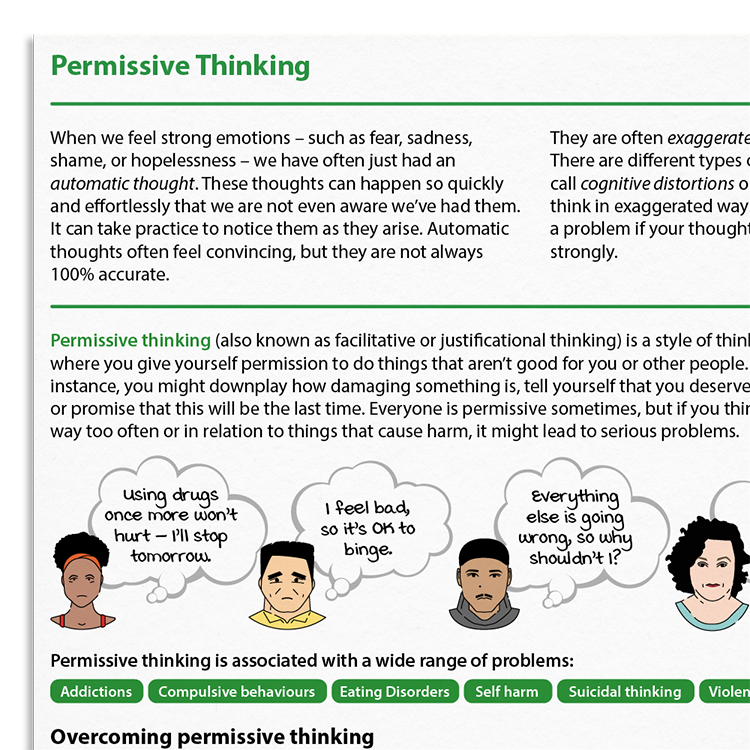

Professional version

Offers theory, guidance, and prompts for mental health professionals. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.

Client version

Includes client-friendly guidance. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.