Guide (PDF)

A psychoeducational guide. Typically containing elements of skills development.

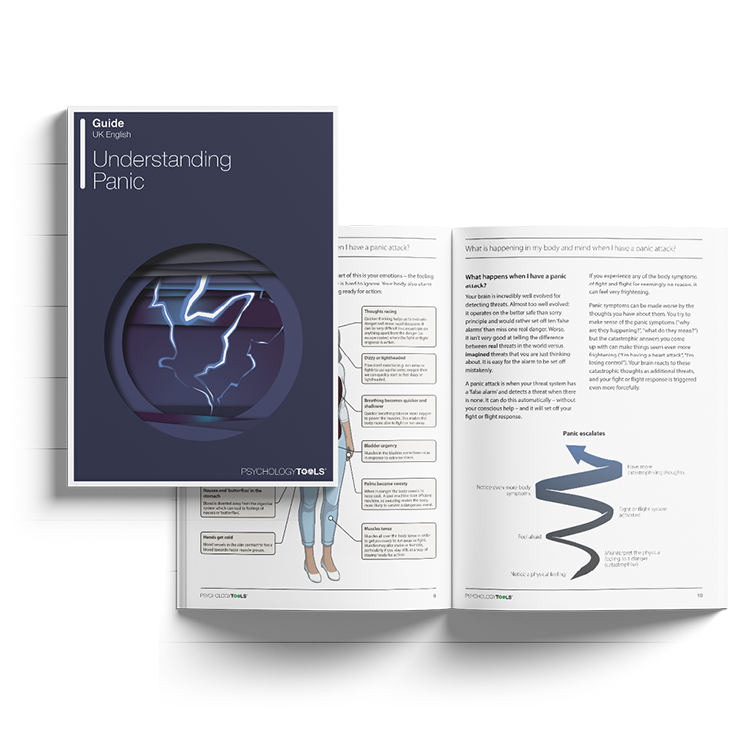

An accessible and informative guide to understanding panic, written specifically for clients.

A psychoeducational guide. Typically containing elements of skills development.

To use this feature you must be signed in to an active account on the Advanced or Complete plans.

Our ‘Understanding…’ series is a collection of psychoeducation guides for common mental health conditions. Friendly and explanatory, they are comprehensive sources of information for your clients. Concepts are explained in an easily digestible way, with plenty of case examples and accessible diagrams. Understanding Panic is designed to help clients suffering from panic attacks and panic disorder understand more about their condition.

This guide aims to help clients learn more about panic attacks and panic disorder (PD). It explains what PD is, what the common symptoms are, and effective ways to address it, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Designed to help clients understand and learn more about PD.

Helps clients explore their experiences with panic.

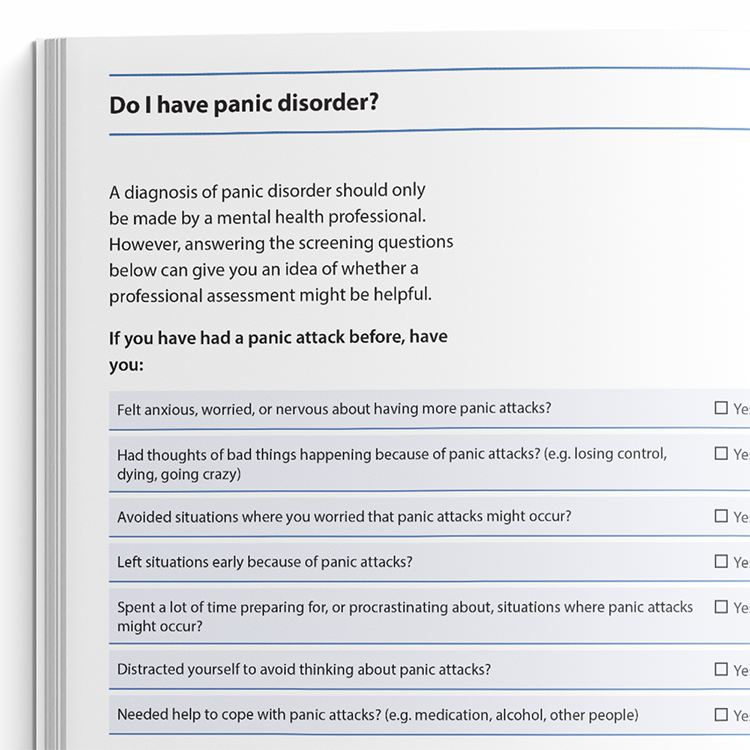

Identify clients who may be experiencing panic disorder (PD).

Provide the guide to clients who could benefit from it.

Use the content to inform clients about PD and help normalize their experiences.

Discuss the client's personal experience with PD.

Plan treatment with the client or direct them to other sources of help and support.

A panic attack is a sudden and intense episode of fear that is typically accompanied by pronounced physiological sensations - such as a racing heart, breathlessness, dizziness, or shaking - and catastrophic interpretations, such as fears of losing control, going crazy, or dying. Although panic attacks are experienced as highly distressing, they are not physically harmful.

Clients who become preoccupied with the fear of future panic attacks and engage in behaviours aimed at avoiding or preventing them may meet diagnostic criteria for panic disorder. This condition is characterised by persistent worry about having further attacks and maladaptive behavioural responses, such as avoidance or safety-seeking.

Epidemiological studies suggest that panic disorder affects approximately 1-3% of the population annually, while isolated panic attacks are even more common. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a highly effective intervention for panic disorder. Evidence indicates that around 80% of individuals who complete a full course of CBT for panic disorder are panic-free at the end of treatment (Rees et al., 2016).

Just enter your name and email address, and we'll send you Understanding Panic (English US) straight to your inbox. You'll also receive occasional product update emails wth evidence-based tools, clinical resources, and the latest psychological research.

Working...

This site uses strictly necessary cookies to function. We do not use cookies for analytics, marketing, or tracking purposes. By clicking “OK”, you agree to the use of these essential cookies. Read our Cookie Policy