Professional version

Offers theory, guidance, and prompts for mental health professionals. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.

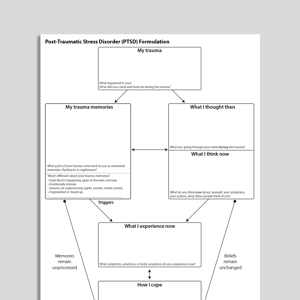

Client version

Includes client-friendly guidance. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.

Editable version (PPT)

An editable Microsoft PowerPoint version of the resource.

![[Free Guide] Critical Illness Intensive Care And Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)](https://assets-media.psychologytools.com/28384/conversions/*---critical_illness_intensive_care_and_ptsd_en-gb_Guides_Cover-preview.png)