Psychology Tools for Overcoming Panic

A comprehensive CBT self-help guide for clients with panic disorder, including worksheets, exercises, and guidance.

Download or send

Overview

Psychology Tools for Overcoming Panic is a structured self-help grounded in the cognitive behavioural approach. It guides clients through understanding and managing panic disorder by breaking down the key psychological mechanisms that maintain panic and offering targeted exercises for change. This manualised intervention is ideal for clinicians seeking a high-quality, session-by-session support tool for clients experiencing panic attacks and persistent anxiety.

Why use this resource?

This resource equips therapists with a practical CBT protocol for treating panic disorder, helping clients to:

- Understand the mechanisms underlying panic attacks.

- Track symptoms, thoughts, and coping strategies.

- Confront symptoms of panic using interoceptive exposure and behavioural experiments.

- Apply structured self-help techniques between sessions to consolidate learning.

Key benefits

Comprehensive

Practical

Flexible

Engaging

What difficulties is this for?

Panic Disorder

For individuals experiencing recurrent, unexpected panic attacks and persistent fear of future episodes.

Agoraphobia

Suitable for those who avoid situations or places due to fears of being unable to escape or get help during a panic-like episode.

Integrating it into your practice

Educate

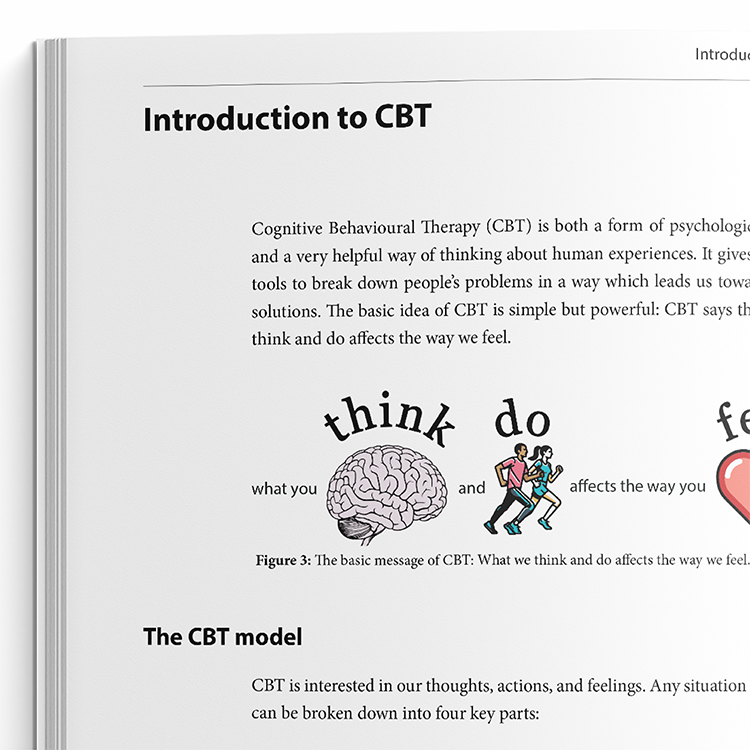

Use the psychoeducation chapters to explain the CBT model of panic.

Monitor

Guide clients to track panic episodes using the panic record forms.

Expose

Use interoceptive and situational exposure tasks to reduce avoidance and fear of body sensations.

Reframe

Help clients challenge catastrophic beliefs using decatastrophising worksheets.

Support

Encourage clients to complete behavioural experiments to test anxious predictions.

Sustain

Use the therapy blueprint section to consolidate learning and plan for relapse prevention.

Theoretical background and therapist guidance

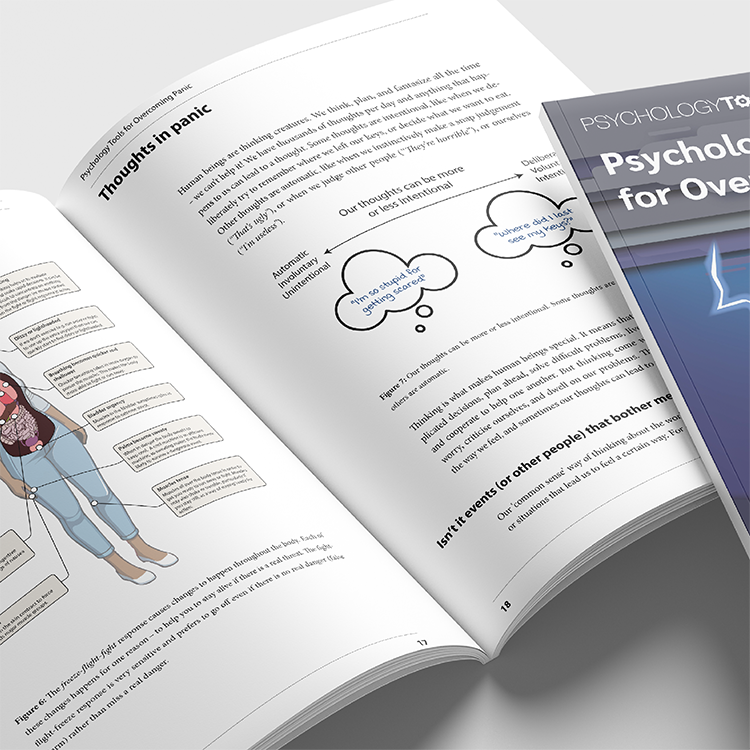

Cognitive behavioral models of panic disorder explain panic attacks as resulting from the misinterpretation of benign bodily sensations. According to David Clark’s (1986) influential cognitive theory, individuals with panic disorder often interpret normal physiological changes – such as a racing heart, dizziness, or shortness of breath – as signs of imminent catastrophe (e.g., a heart attack, fainting, or losing control). These catastrophic misinterpretations escalate anxiety, intensify physical symptoms, and reinforce the person’s fears, creating a self-perpetuating cycle. The model emphasizes the role of both cognitive misappraisals and maintaining behaviors such as avoidance or excessive monitoring of bodily cues. Treatment grounded in this model uses techniques like cognitive restructuring and behavioral experiments to help clients evaluate and revise their anxious predictions (Clark, 1986; Clark et al., 1994).

Developed contemporaneously, Barlow’s panic control treatment (PCT) describes a broad conceptualisation of vulnerability. PCT proposes that panic disorder arises from the interaction of three key vulnerabilities: a generalized biological vulnerability, a generalized psychological vulnerability (often formed through early experiences of uncontrollability or unpredictability), and a specific psychological vulnerability toward interpreting somatic sensations as dangerous (Barlow, 2002). These factors create the conditions for a “false alarm” – a panic response occurring in the absence of actual threat. Repeated fear of these internal cues may result in behavioral strategies like interoceptive avoidance, which ultimately maintain the disorder. PCT addresses these processes through psychoeducation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, and interoceptive exposure – exercises in which clients deliberately evoke and learn to tolerate feared sensations (Barlow et al., 1989; Barlow & Craske, 2000).

This resource draws on both Clark’s cognitive model and Barlow’s integrative approach to offer a comprehensive CBT intervention for panic disorder. Clients first receive psychoeducation to help normalize bodily symptoms of anxiety and to understand how misinterpretation and avoidance reinforce panic. Structured exercises support clients in challenging catastrophic thoughts, reducing safety behaviors, and reappraising their bodily experiences. Interoceptive exposure is used not just to extinguish fear, but to build corrective learning: clients discover firsthand that panic-related sensations are safe, manageable, and temporary. Additional tools – such as self-monitoring forms, weekly skill-building assignments, and relapse prevention strategies – help consolidate gains and promote long-term recovery.

What's inside

- Psychoeducation covering panic disorder and CBT models.

- Worksheets for panic tracking, mood monitoring, and behavioural experiments.

- Decatastrophizing tools and interoceptive exposure exercises.

- Patient stories and therapist guidance for delivering interventions.

- Structured weekly practice forms and relapse prevention planning.

FAQs

How this resource helps improve clinical outcomes

This workbook facilitates greater client insight into panic mechanisms and offers structured interventions that:

- Decrease avoidance and safety behaviours.

- Increase tolerance of bodily sensations.

- Reduce fear of future panic attacks.

- Promote long-term behavioural change and relapse prevention.

Clinicians benefit from a flexible, ready-to-use format that enhances client engagement and promotes adherence to a CBT framework.

References and further reading

- Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Barlow, D. H., Craske, M. G., Cerny, J. A., & Klosko, J. S. (1989). Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behavior Modification, 13(2), 163-205. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455890132003

- Barlow, D. H., & Craske, M. G. (2000). Mastery of your anxiety and panic: Therapist guide (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Clark, D. M. (1986). A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(4), 461-470. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(86)90011-2

- Clark, D. M., Salkovskis, P. M., Hackmann, A., Wells, A., & Gelder, M. (1994). Brief cognitive therapy for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 583-589. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.62.3.583

Just enter your name and email address, and we'll send you Psychology Tools For Overcoming Panic (English US) straight to your inbox. You'll also receive occasional product update emails wth evidence-based tools, clinical resources, and the latest psychological research.

Product

Company

Support

- © 2026 Psychology Tools. All rights reserved

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Disclaimer

Working...

We value your privacy

This site uses strictly necessary cookies to function. We do not use cookies for analytics, marketing, or tracking purposes. By clicking “OK”, you agree to the use of these essential cookies. Read our Cookie Policy