Guide (PDF)

A psychoeducational guide. Typically containing elements of skills development.

An accessible and informative guide to understanding post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), written specifically for clients.

A psychoeducational guide. Typically containing elements of skills development.

To use this feature you must be signed in to an active account on the Advanced or Complete plans.

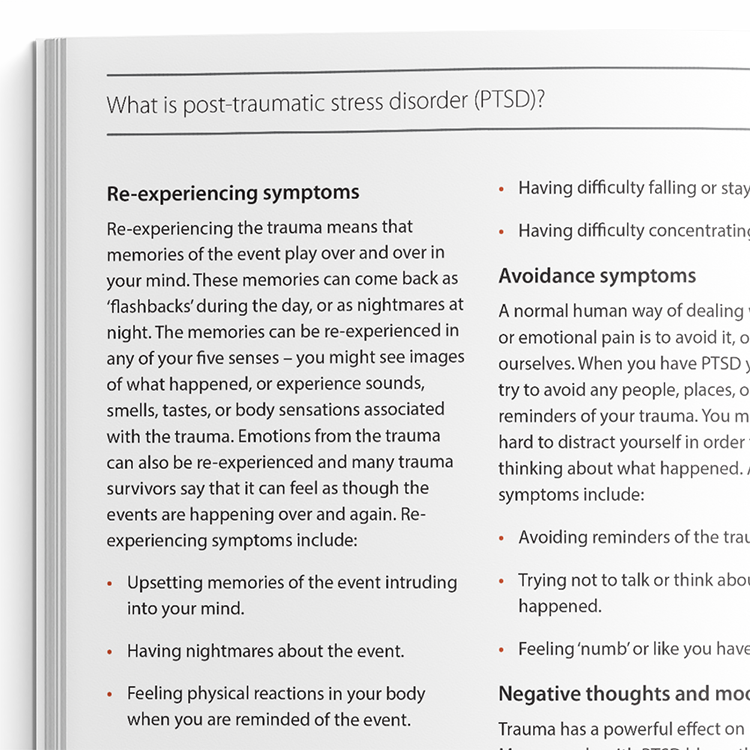

Our ‘Understanding…’ series is a collection of psychoeducation guides for common mental health conditions. Friendly and explanatory, they are comprehensive sources of information for your clients. Concepts are explained in an easily digestible way, with plenty of case examples and accessible diagrams. Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is designed to help clients with PTSD and Complex PTSD to understand more about their condition.

This guide aims to help clients learn more about post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It explains what PTSD is, what the common symptoms are, and effective ways to address it, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Designed to help clients understand and learn to more about PTSD.

Identify clients who may be experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Provide the guide to clients who could benefit from it.

Use the content to inform clients about PTSD and help normalize their experiences.

Discuss the client's personal experience with PTSD.

Plan treatment with the client or direct them to other sources of help and support.

Experiencing trauma is a common part of many individuals' lives. While the majority of people gradually recover from traumatic events without the need for professional intervention, a significant proportion develop longer-lasting psychological difficulties. When the effects of trauma persist and cause substantial distress or impairment, clients may meet criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Epidemiological data suggest that approximately 3-5% of the population will experience PTSD in any given year. Encouragingly, a range of evidence-based psychological therapies are available for PTSD, offering effective pathways to recovery for many individuals.

Just enter your name and email address, and we'll send you Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (English US) straight to your inbox. You'll also receive occasional product update emails wth evidence-based tools, clinical resources, and the latest psychological research.

Working...

This site uses strictly necessary cookies to function. We do not use cookies for analytics, marketing, or tracking purposes. By clicking “OK”, you agree to the use of these essential cookies. Read our Cookie Policy