Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT)

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT) is a form of psychotherapy developed by Paul Gilbert for people struggling with shame and self-criticism. It is an integration of ideas concerning: Jungian archetypes; evolutionary approaches to human behavior, suffering, and growth; neuroscientific and cognitive-behavioral ideas about the way that people think and behave; and Buddhist philosophy concerning compassion and mindfulness (Gilbert, 2009, 2010, 2014). There is considerable evidence that developing self-compassion is associated with a wide range of benefits including the ability to build positive relationships, increased physical and mental well-being, or the ability to manage voices in psychosis.

What Is Compassion, Why Do I Need It, And How Might It Help Me?

What Is Compassion, Why Do I Need It, And How Might It Help Me?

Receiving Compassion From Your Ideal Other

Receiving Compassion From Your Ideal Other

Trying On The Qualities Of Compassion

Trying On The Qualities Of Compassion

Combining Soothing Breathing With A Soothing Smell

Combining Soothing Breathing With A Soothing Smell

Breathing To Activate Your Soothing System

Breathing To Activate Your Soothing System

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Mindfulness

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Mindfulness

Motivational Systems (Emotional Regulation Systems)

Motivational Systems (Emotional Regulation Systems)

What Is Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT)?

What Is Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT)?

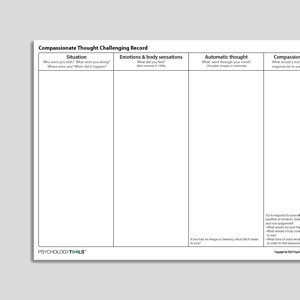

Compassionate Thought Challenging Record

Compassionate Thought Challenging Record

Links to external resources

Psychology Tools makes every effort to check external links and review their content. However, we are not responsible for the quality or content of external links and cannot guarantee that these links will work all of the time.

Case Conceptualization / Case Formulation

- Formulation in Compassion Focused Therapy | Paul Gilbert | 2007

- Training our minds in, with, and for compassion: an introduction to concepts and compassion-focused exercises

Exercises

- Writing a compassionate letter to myself

- Compassionate Letter Writing (Therapist Notes and Client Handout) | Paul Gilbert | 2007

- Compassionate letter writing | Paul Gilbert | 2010

- Building a compassionate image | Compassionate Mind Foundation

Guides and workbooks

- How to develop self-compassion | Russ Harris

Information (Professional)

- Healthy emotion regulation strategies pyramid | Alice Boyes | 2011

Presentations

- An introduction to compassion focused therapy and compassion focused ACT for anxiety and depression | Dennis Tirch & Laura Silberstein Tirch | 2016

- An Introduction to the Theory & Practice of Compassion Focused Therapy and Compassionate Mind Training for Shame Based Difficulties | Paul Gilbert | 2010

- Compassion focused therapy: self-criticism | Paul Gilbert | 2017

- Compassion focused therapy: Is compassion an antidote to shame and an effective phase in the treatment of complex PTSD? | Deborah Lee | 2017

- Introducing compassion focused therapy | Paul Gilbert

Treatment Guide

- Compassionate Friend Group: Facilitator manual | Isabel Clark

- The ‘Compassionate Friend’ group: A 3 session group designed for use in a ward environment | Isabel Clark

- Training our minds in, with, and for compassion: an introduction to concepts and compassion-focused exercises | Paul Gilbert | 2010

Video

- Compassion, anger, strength, and moral indignation | Russel Kolts | 2020

- Relating to voices using CFT | Charlie Herriot-Maitland

- The compassionate kit bag | Kate Lucre, Neil Clapton | 2019

-

CFT Workshop at CCARE

| Paul Gilbert | 2013

- Part 1

- Part 2

- Part 3

- Part 4

- Tragedies of the human mind: DCP lecture | Paul Gilbert | 2015

- Introduction to CFT: Meng Wu Lecture | Paul Gilbert youtube

- Compassion for voices: a tale of courage and hope | Charlie Heriot-Maitland, Kate Anderson youtube

Websites

- Exercises to increase self compassion | Neff, K.

Recommended Reading

- Goss, K., & Allan, S. (2010). Compassion focused therapy for eating disorders. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(2), 141-158 suomensyomishairioyhdistys.fi

- Compassion Focused Therapy – Procedure Outline

- Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15, 199-208 archive.org

What Is Compassion Focused Therapy?

Assumptions of CFT

human brains/minds have evolved and have evolved needs (e.g., affection, care, protection, belonging), competencies (e.g., mentalizing, empathy, ability for fantasy) and drives (e.g., seeking safety, achieving dominance). These needs/competencies/drives are associated with different brain systems (old brain / new brain);

human beings have ‘social mentalities’ that enable them to seek out and form certain types of relationships. In these mentalities or ‘mind sets’ we are motivated to engage in different types of behavior, e.g., care-giving, care-seeking, safety-seeking, achievement-seeking;

the ability to self-soothe is linked to our attachment experiences;

humans have at least three types of emotional regulation systems: threat-focused and protection and safety-seeking; drive, excitement, and vitality; affiliative-focused soothing system;

distress and dysfunction may arise from problematic inputs into the emotion regulation systems (e.g., being made homeless, being trapped in an abusive relationship) or because of dysregulation of the systems (e.g., poorly developed self-soothing abilities);

the soothing system is our brain’s natural ‘threat regulator,’ which can be activated by disengaging from internal stimulators of threat (e.g., rumination, self-criticism) or by distancing oneself from one’s inner emotions (e.g., via mindfulness). Once activated this system can be used to approach aversive inner experiences in a compassionate frame of mind.

Procedures and Techniques in CFT

psychoeducation to understand our evolved minds/brains (old brain / new brain);

the use of mindfulness techniques to compassionately ‘stand back’ from turbulent cognitions and emotion;

the practice of self-soothing techniques to physiologically change one’s state in order to access different social mentalities;

to develop self-compassion using imagery in order to activate the brain’s natural threat regulator;

the use of the (above described) ‘compassionate foundation’ as a base from which to explore and engage with aversive or traumatic inner experiences.

References

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15(3), 199–208.

Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy. CBT Distinctive Features Series. New York: Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41.