The Therapist’s Guide To Recognizing Bipolar Disorder

Jump to

What is bipolar disorder?

Bipolar disorder is the name given to a group of mental health problems that cause fluctuations in mood and behavior. Everyone experiences variations in their mood but in bipolar the highs and lows are extreme and are beyond what would be considered normal for that person. The changes in mood can be extremely distressing: a recent review of the first-person accounts of people with bipolar disorder revealed profound experiences of loss, stigma, uncertainty, and despair [1]. Patients described how threatening it feels to receive a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, worry about relapsing, and the severe impacts bipolar disorder can have upon relationships and their ability to function [1].

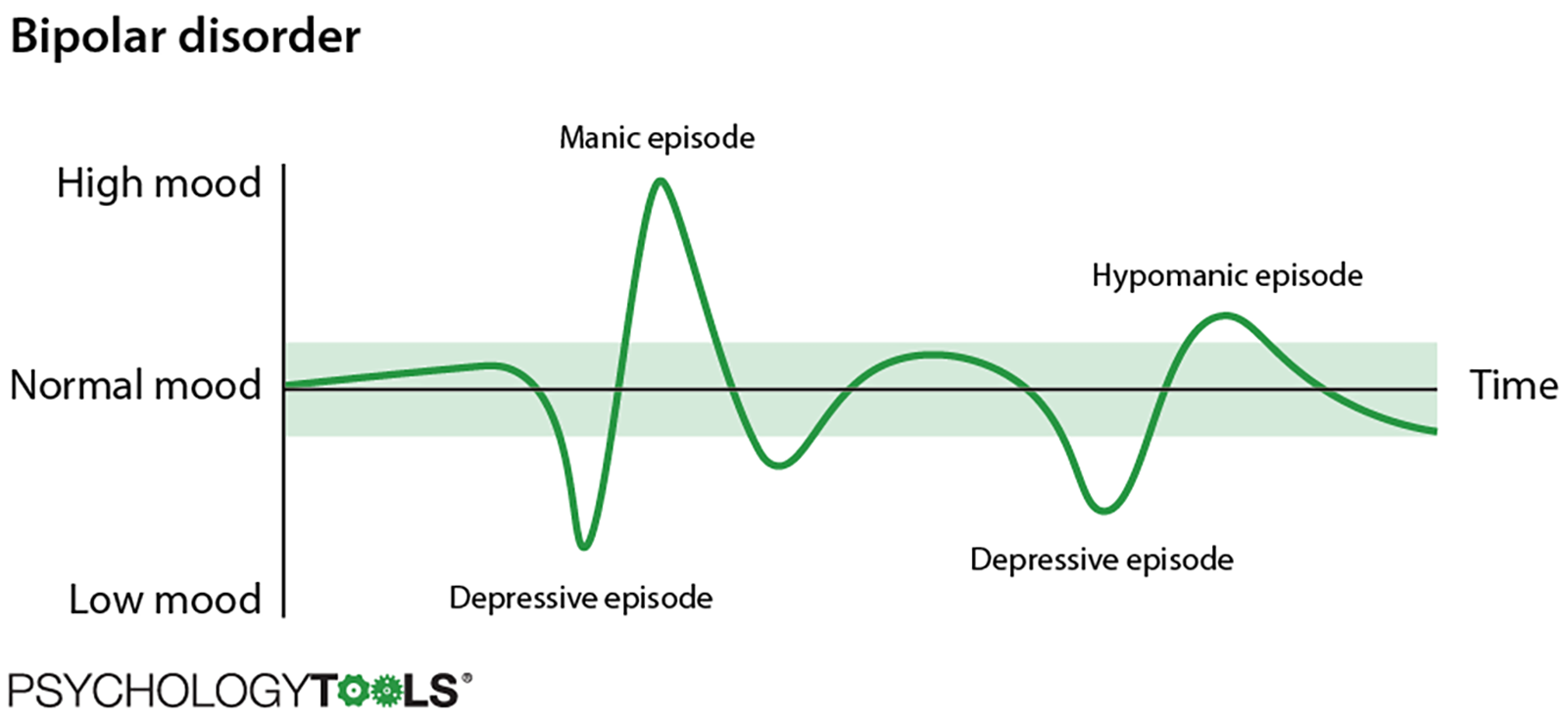

Figure 1: An illustration of manic, hypomanic, and depressive mood episodes in bipolar disorder.

The highs of bipolar disorder are called ‘manic’ or ‘hypomanic’ episodes and the lows are called ‘depressive’ episodes. The term ‘bipolar’ just refers to the way that mood can change between the two extremes and different types of bipolar disorder are diagnosed depending upon which combination of mood states are experienced. People with bipolar disorder experience increased rates of mortality – the World Health Organisation estimates that they are 35-100% higher than the general population [2], and up to 15% of people with bipolar end their own lives [3]. One critical problem is that many individuals with bipolar disorder experience extremely long delays before receiving formal diagnosis and appropriate treatment. The average delay from first presentation to a medical professional until receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is nine years [4]. It is therefore essential that clinicians feel confident in recognizing bipolar symptoms in order to minimize this delay.

Jeremy often has periods where he feels low and uninterested in the things that normally get him excited. When his mood is low, he isolates himself from his friends and withdraws from the world. Jeremy also experiences periods where he feels on top of the world and capable of anything. When he was eighteen he went through a period where he struggled very badly with suicidal thoughts. He spoke to his doctor, expressing his particular concern about his suicidal ideation, and was diagnosed with depression. It was only five years later, after his hypomanic episodes were recognized by a specialist, that Jeremy was diagnosed with bipolar II.

Even expert clinicians experience difficulties in recognizing and treating bipolar disorder:

- It is difficult for clinicians to differentiate bipolar from unipolar depression. One survey of bipolar patients indicated that 69% were misdiagnosed, with the most frequent misdiagnosis being unipolar depression [5].

- There is a reporting bias towards depressive episodes, and depression symptoms occur more frequently than manic or hypomanic episodes. Clients are more likely to present to services during depressed periods than during hypomanic or manic episodes, and individuals with bipolar often spend more of their lives in a depressed, rather than manic or hypomanic state [6, 7].

- Symptoms of bipolar are particularly difficult to recognize in adolescents and children because fluctuations in mood and energy are more common at this life stage [8].

- The DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic manuals differ in the way that they classify bipolar disorders. Non-expert clinicians often report that diagnosis of bipolar are among the most complex to make.

- Symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD) are often misdiagnosed as bipolar. A study of patients with BPD revealed that almost 40% had been misdiagnosed, with bipolar disorder being a frequent misdiagnosis [9].

- If hallucinations are present, then bipolar presentations are much more likely to be misdiagnosed as another condition. Clinicians often use heuristic ‘short-cuts’ to arrive at diagnoses, and hallucinations which can be a part of bipolar disorder can lead to misdiagnosis [10].

Given all of these complexities it is unsurprising that non-specialists struggle to recognize symptoms of bipolar disorder. Our goal is to help you to understand the important features of bipolar disorder and to overcome some of the common pitfalls that clinicians face when assessing clients who report symptoms of bipolar.

The building blocks of bipolar disorder

Diagnoses of bipolar and related disorders are made based on the presence of episodes of hypomania, mania, or depression. In order to confidently identify bipolar, it is essential that clinicians understand the ‘ingredients’ which comprise the different bipolar diagnoses.

What is a ‘normal’ mood?

It would be a mistake to think that ‘normal’ moods are steady. We all have moods that fluctuate – some days we feel motivated, energetic, and ready to engage with the world, and other days we just want to curl up and hide away. Many of these fluctuations happen in response to things that are happening in our lives, but our moods can fluctuate with the seasons, our health, or our hormonal cycle [11, 12]

What is a manic episode?

A manic episode is a period of ‘high’ mood. Someone having a manic episode might feel euphoric with a great sense of well-being, confident and adventurous, have an increase in sexual energy, and feel excited as though they can’t express ideas quickly enough. The way we feel affects the way we act, so when someone having a manic episode feels this way they are prone to behave in ways that are unusual for them such as being more outgoing or talkative, being much more active than normal, sleeping much less than before, being rude or aggressive, or even taking risks with their safety.

At the severe end of a manic episode, some people experience psychotic symptoms such as delusions or hallucinations. They may for example develop odd beliefs with concerns that they are being watched or followed, or that they understand things that other people don’t. Someone having a manic episode might see or hear things that other people can’t. Manic episodes can be very serious and in some cases may require hospitalization.

What Is A Hypomanic Episode?

A hypomanic episode is essentially a milder version of a manic episode. The mood and behavior changes seen in a hypomanic episode are not as extreme and they often do not last as long as a manic episode, although the emotional and behavioural changes are still definitely abnormal for the individual. Hypomanic episodes can feel more manageable than manic episodes and may not interfere so much with daily life, although other people may notice changes in the individual’s behavior.

What Is A Depressive Episode?

Everyone has periods of low mood and these are especially common when we experience losses or struggle with other challenges in our lives. According to formal diagnostic criteria, a depressive episode is more severe and persists for longer than normal downward fluctuations in our mood. A depressive episode is a two-week period where five or more of the following depressive symptoms are present: a depressed mood, diminished interest in activities, lack of energy or fatigue, sleep disturbances, suicidal thoughts or behavior, loss of confidence or feelings of worthlessness, or psychomotor agitation.

What is a mixed episode?

A mixed episode is a mixture of depressive and manic / hypomanic symptoms, or a rapid alternation between them. Individuals with bipolar often report that these are the most difficult episodes to cope with as they can be highly unpredictable and confusing for the individual to process.

Symptoms of a manic episode |

Symptoms of a hypomanic episode |

Symptoms of a depressive episode |

|

|

|

Table 1: Symptoms of manic, hypomanic, and depressive episodes.

Recognizing bipolar disorder

Diagnoses of bipolar disorder are made by identifying different combinations of the ‘ingredients’ of manic, hypomanic, depressive, and mixed episodes. The DSM-5’s categorizations of ‘bipolar I’, ‘bipolar II’ and ‘cyclothymia’ form the most up-to-date diagnostic classification [12] with the ICD-10 using the alternative terminology of ‘bipolar affective disorder’ [14]. it is likely however that there will be more concordance between the two diagnostic systems with the publication of the ICD-11.

Bipolar I

A diagnosis of bipolar I requires one lifetime manic episode to have occurred. Only a minority (around 5-16%) of those with bipolar I exhibit ‘unipolar’ mania and a much more common presentation is manic episodes ‘bookended’ by depressive or hypomanic episodes [15].

Bipolar II

Bipolar II requires at least one lifetime hypomanic episode and at least one major depressive episode to have occurred. The occurrence of a manic episode is an exclusion criterion for a diagnosis of bipolar II and some clients find that their diagnosis of bipolar II is changed to bipolar I during the course of their illness. Bipolar II is commonly misdiagnosed as unipolar depression since detection of a hypomanic episode can be more difficult than a manic episode due to its less severe impact on functioning [15, 6, 16].

Cyclothymic Disorder

Cyclothymic disorder, or cyclothymia, is a chronic fluctuating mood disorder with numerous periods of mild hypomanic and mild depressive symptoms that are distinct from one another. Diagnostic criteria require that the periods must never have been severe enough to meet the full criteria for a hypomanic, manic, or depressive episode thus making it more difficult to recognize than bipolar disorder. Because of this, cyclothymic disorder frequently goes undiagnosed [17].

Bipolar affective disorder

Instead of bipolar I and bipolar II the ICD-10 recognizes ‘bipolar affective disorder’. For a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder at least two lifetime episodes (manic, hypomanic, depressive, or mixed) must have occurred with at least one being manic or hypomanic. The diagnosis is typically sub-categorized according to the current affective episode the individual is experiencing.

Comorbidity

Bipolar disorder is associated with significant comorbidity. In particular, there is substantial overlap between bipolar disorder and alcohol and substance misuse. Rate of alcohol and substance misuse have been reported to be as high as 69%, with average rates thought to be around 30%. Rates of anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) are also much higher than typical background levels [18].

Improving recognition of bipolar disorder in your clinical practice

Ruling out bipolar disorders should be a routine part of the workup for all patients who present acutely with depressive symptoms or who report a history of depressionNeil S. Kaye, MD

Accurately diagnosing bipolar disorder in clinical practice can be difficult. Given the high rates of misdiagnosis it is incumbent upon clinicians to do all they can to familiarize themselves with the condition. Here are some practical steps you can take to help you to identify symptoms of bipolar disorder in your clients.

- Recognize that bipolar is often misdiagnosed as unipolar depression. Just knowing how frequently bipolar disorder is misdiagnosed means that you are more likely to ask the essential disambiguating questions that will allow you to accurately conceptualize your client’s difficulties.

- Familiarize yourself with the ‘ingredients’ and full diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder. Research indicates that clinicians use heuristic biases (mental ‘short cuts’) which can lead to misdiagnosis [19].

- Know that client reports of ‘frequent ups and downs’ are the most powerful predictor of bipolar disorder. Taking the time to explore what your clients mean when they describe having ‘ups and downs’ is an important way that you can understand what they are struggling with [20].

- Use specific questions to explore whether your client has a history of mania, for example “would you say that you are one of those people who have frequent ups and downs?”. Explore even minor symptoms which point towards mania such as elevated mood, irritability, or racing thoughts [20].

- Consider your client’s response to previous treatment. Patients with bipolar disorder may respond less effectively to anti-depressants than those with unipolar depression [7, 16].

- Look at the history of your client’s illness. It is more common for those with bipolar to experience depressive symptoms at an earlier age [7].

- Ask about life complications. Highly turbulent or complicated lives such as multiple marriages, or bankruptcy may indicate bipolarity [7].

- Ask about their family history of bipolar as well as other mental health disorders such as schizophrenia which are a risk factor for bipolar disorder [7].

- Structured interviews are the most reliable way to obtain a bipolar diagnosis [21] but some self-report measures may be helpful. The General Behavior Inventory (GBI [22]) and the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ [22]) are both recommended [24].

References

[1] Warwick, H., Mansell, W., Porter, C., & Tai, S. (2019). ‘What People Diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Experience as Distressing’: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Journal of Affective Disorders. In press.

[2] World Health Organiation Information Sheet: Premature death among people with severe mental disorder. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/info_sheet.pdf

[3] Simpson SG., & Jamison KR. (1990). The risk of suicide with bipolar disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(2): 53-56

[4] Fritz, K., Russell, A. M., Allwang, C., Kuiper, S., Lampe, L., & Malhi, G. S. (2017). Is a delay in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder inevitable? Bipolar disorders, 19(5), 396-400.

[5] Hirschfeld, R., Lewis, L., & Vornik, L. A. (2003). Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

[6] Phillips, M. L., & Kupfer, D. J. (2013). Bipolar disorder diagnosis: challenges and future directions. The Lancet, 381(9878), 1663-1671.

[7] Muzina, D. J., Kemp, D. E., & McIntyre, R. S. (2007). Differentiating bipolar disorders from major depressive disorders: treatment implications. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 19(4), 305-312.

[8] Singh, M. K., DelBello, M. P., & Strakowski, S. M. (2008). Temperament in child offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 18(6), 589-593.

[9] Ruggero, C. J., Zimmerman, M., Chelminski, I., & Young, D. (2010). Borderline personality disorder and the misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44(6), 405-408.

[10] Meyer, F., & Meyer, T. D. (2009). The misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder as a psychotic disorder: some of its causes and their influence on therapy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 112(1-3), 174-183.

[11] Steiner, M., Dunn, E., & Born, L. (2003). Hormones and mood: from menarche to menopause and beyond. Journal of Affective Disorders, 74(1), 67-83.

[12] Huibers, M. J., de Graaf, L. E., Peeters, F. P., & Arntz, A. (2010). Does the weather make us sad? Meteorological determinants of mood and depression in the general population. Psychiatry Research, 180(2-3), 143-146.

[13] American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

[14] World Health Organization. (1993). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization.

[15] Strakowski, S. M. (2012). Bipolar disorders in ICD-11. World Psychiatry, 11(Suppl 1), 31-6.

[16] Kaye, N. S. (2005). Is your depressed patient bipolar? The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 18(4), 271-281.

[17] Van Meter, A. R., Youngstrom, E. A., & Findling, R. L. (2012). Cyclothymic disorder: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(4), 229-243.

[18] Krishnan, K. R. R. (2005). Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosomatic medicine, 67(1), 1-8.

[19] Wolkenstein, L., Zwick, J. C., Hautzinger, M., & Joormann, J. (2014). Cognitive emotion regulation in euthymic bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 160, 92-97.

[20] Hauser, M., Pfennig, A., Özgürdal, S., Heinz, A., Bauer, M., & Juckel, G. (2007). Early recognition of bipolar disorder. European Psychiatry, 22(2), 92-98.

[21] Akiskal HS. Classification, diagnosis, and boundaries of bipolar disorders: A review. In: Maj M, Akiskal HS, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Sarotius N, editors. Bipolar disorder. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2002. pp. 1–52.

[22] Depue RA, Slater JF, Wolfstetter-Kausch H, Klein D, Goplerud E, Farr D. (1981). A behavioral paradigm for identifying persons at risk for bipolar depressive disorder: A conceptual framework and five validation studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90:381–437.

[23] Hirschfeld RMA, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Calabrese JR, Flynn L, Keck PE, Jr, et al. (2000). Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157:1873–1875.

[24] Miller, C. J., Johnson, S. L., & Eisner, L. (2009). Assessment tools for adult bipolar disorder. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 16(2), 188-201.