Grief, Loss, and Bereavement

Loss is something that binds us together as human beings, and grief is a part of life that all of us will experience when we suffer loss, whether it takes the form of someone’s death, losing a job, a relationship, hopes, dreams, or other things that you value.

Powerful feelings of grief and loss are so normal and natural that they are typically not given a ‘diagnosis’ like other conditions such as anxiety or depression. There is no right way to grieve and no ‘quick fix’, but there are ways that you can help yourself to come to terms with your loss.

When you have experienced loss, it is natural to feel a wide range of emotions, and you might feel overwhelmed by grief. Grief is a powerful emotional and physical reaction to the loss of someone or something. It is characterized by deep feelings of sadness and sorrow, and often by a powerful yearning or longing to be with that person again. Other effects of grief include feeling numb and empty, as if there is no meaning to anything, or being annoyed at yourself for how you are feeling compared to how you ‘should’ be dealing with things. You might feel angry that your loved one has gone and left you behind. Perhaps others are expecting you to be moving on and this is making you feel worse. You may also be worried that you will never feel better, or that you will not be able to cope.

Grief is also felt physically: you might be struggling to eat or sleep, or might feel sick in your stomach. These feelings may come in waves, and you may be tossed from one to another. All of these feelings are a normal part of grieving. Despite the pain, the process of grieving is an important part of how we come to terms with loss.

Powerful feelings of grief and loss are so normal and natural that they are typically not given a ‘diagnosis’ like other conditions such as anxiety or depression. There is no right way to grieve, and unfortunately, no quick fix.

Although there are no short-cuts, there are things you can do to help yourself along the way. Judging and comparing yourself to how you ‘should’ be feeling can add to your suffering and pain. Start by learning to be patient, kind and understanding with yourself, like you would with a dear friend. This is a difficult journey, and treating yourself kindly can support you along the way.

What is it like to grieve?

Gloria and Mario

Gloria was 62 when her husband Mario died from prostate cancer. Unfortunately, his cancer was only diagnosed once it was in a fairly advanced stage. Mario had surgery and underwent hormone therapy and chemotherapy. Gloria was by Mario’s side every day and hoped and prayed that he would recover, but he got weaker and weaker with each treatment. He was ill for nearly two years before he was eventually moved to a hospice three weeks before he died. Gloria knew then that her husband would never return home.

Gloria and Mario had been married for forty-two years and had three children and six grandchildren. They had their ups and downs during their life together, and it hadn’t always been easy. Mario used to like having a drink and this had been an ongoing tension for them for as long as they had been together. However, despite these challenges they loved each other dearly and were looking forward to all the things they would do in retirement together when Mario became ill.

Gloria then became his carer, which was difficult for them both as Mario had always been a very independent man. As the cancer spread, he got weaker and required more and more help each day. There were times when Gloria found it tiring and demanding caring for Mario, although she never complained and tried not to show how it was affecting her. When he was moved to the hospice, she felt many different emotions. She was scared and knew his death was imminent, and she was worried how she would cope without him. On the other hand, she also felt relief that she didn’t have the physical demands of caring for him round the clock. This made her feel guilty, and she felt ashamed for having such a thought.

While Mario was in the hospice, Gloria was there every day. She would read to him, play his favourite music, and helped the nurses to care for him. On the day he died, Gloria had left the hospice to buy cakes for the nurses. When she returned, she found Mario had died – the nurses told her that he had slipped away peacefully. Gloria felt awfully guilty for not being by his side in his last moments, and this was something that she kept playing over in her mind.

Gloria’s life and home felt empty without Mario. For a while after he died the house was busy with her family, and she was kept busy with planning for the funeral. When things became quieter afterwards, she felt helpless and didn’t quite know what to do with herself. The past years had been so busy each day caring for Mario that Gloria couldn’t remember what life was like before. There was also part of her that felt relief that he was no longer suffering and in pain.

As Mario had been unwell for some time, Gloria thought that she would be, to some extent, prepared for his loss. However, she was shocked by the deep despair and yearning she felt for him once he died. She often replayed regrets in her mind, all the things she wishes she had said and done. She wished she hadn’t argued with him about his drinking and hoped he didn’t go with the memories of her nagging him. She thought about the future they would never have. She couldn’t imagine what her life would be like without him.

Gloria tried to keep herself busy to distract from her pain. Fortunately, her children and grandchildren lived nearby, and she was able to throw herself into their lives and helping with childcare. Her children told her how strong she was and praised her for the way she was dealing with things. However, she knew on the inside the effort it was taking to supress how she was really feeling. When she heard his favourite song on the radio she would feel like she had been hit in the stomach. Keeping busy helped Gloria get through the days, however at night she would lie awake, unable to sleep. She would feel a deep longing for Mario and the life they had planned in their retirement. Gloria started to feel very fatigued from all the business and lack of sleep. Eventually her grief started to catch up with her and she felt consumed by it. She couldn’t get up in the mornings and felt like all the joy had been drained from her life.

Aspects of counseling that Gloria found helpful

Gloria saw a bereavement counselor after her daughter suggested that she might find it helpful to speak to someone. In counseling Gloria felt listened-to. She started to talk about how much she was struggling. She felt like her counselor wasn’t judging her, and let her tell her story. Gloria found it helpful to tell her counselor about her life with Mario and how he had died. Gloria shared her regrets about not being with him when he died, and the guilt she felt for having felt relief when he passed. Her counselor helped Gloria to see that these were normal reactions. This helped Gloria to forgive herself and her attitude towards herself became kinder.

In counseling Gloria also shared her fears about the future. When she looked ahead everything felt bleak and dark. She felt useless, her children were all grown and didn’t need her as much as they used to. She couldn’t imagine what life would be like without Mario. Gloria also felt guilty and didn’t want to let go of Mario or move on without him. Gloria’s counselor helped her to realize that grieving wasn’t about letting go or moving on, but instead learning to live without Mario while also carrying him in her heart.

She also found it helpful to learn about different ways of understanding what she was going through. She learned that suppressing her feelings and ‘being strong’ was getting in the way of her processing her emotions. She found it useful to talk to her children about this, as they had unknowingly encouraged her to ‘act strong’. It also helped them to open about their grief, and as a family they started to think about ways to remember Mario and keep him alive in their hearts and memories. She worried about how she would cope on his birthday, but the family all got together and celebrated his life.

Gloria’s counselor encouraged her to talk about the life she had with Mario, and all the good memories they had together. Gloria made a memory book to put together all the photos and things that reminded her of Mario. She enjoyed finding ways to remember him and felt relieved to not be so consumed by guilt. It took time, but Gloria was able to start thinking about her future. She started trying new hobbies and seeing her friends more regularly. Whenever she felt guilty, she would imagine what Mario would say to her, which helped her to feel better. She knew he would want her to live a full and happy life and would want her to enjoy her retirement. Gloria still had her ups and downs, but no longer felt unable to carry on.

What is loss?

When we talk about loss we often mean the death of someone that we love. It is important to acknowledge that people can also experience grief when confronted with other losses such as: the breakup of a relationship, the loss of an important role such as a job, or the diagnosis of a life-changing illness. For much of this guide we will refer to bereavement, but most of it is relevant other losses too.

Losses within the loss

When someone dies you might experience many losses. Part of grieving is about recognizing what you have lost, and loss comes with many changes that are not always immediately visible. There is the physical loss of the person and their presence, and other less tangible losses such as:

- The loss of a shared life, consisting of the things you did together and for each other.

- The loss of a shared future together, including all of your shared hopes, dreams, and plans for the future.

- The loss of your shared social life.

- The loss of all that your loved one did for you. They might have been the one who fixed problems around the house, or who managed your finances.

Characteristics of the loss

Not all losses are the same and not all losses affect us in the same way. The circumstances of the loss can affect how you grieve. Some of the characteristics of the loss that can affect how you grieve include:

- The manner of the death and whether you had time to prepare

- Anticipated and expected. For example, you may have known that your loved one was going to pass after a long illness. Their death may not have had any less impact, but in these circumstances some people notice that they started to grieve before the person died, or when they learnt of the illness.

- Sudden and unexpected. You may have lost your loved one unexpectedly from a health event, or from an accident. It is normal to be in a state of shock and disbelief, as your mind and body tries to understand what has happened.

- Traumatic or violent. Your loved one may have died violently or by suicide. In these circumstances there are often additional layers of shock and grief.

- The type of relationship you had

- The type and quality of relationship you had with the person can affect the kind of grief you experience. The degree of emotional closeness, the role that this person played in your life, and your feelings for them while they were alive are all factors that can influence how you grieve for them.

- Other people’s reactions

- The way that other people react can support or hinder your grieving. People around us often want us to feel better, but this can sometimes mean that they fail to give us the space to actually talk about how we are feeling.

- What else is going on in your life?

- The other things that are going on in your life can affect how much space you have to grieve. You might feel under pressure to care for others, to carry on as normal, or return to work sooner than you might like.

What is grief?

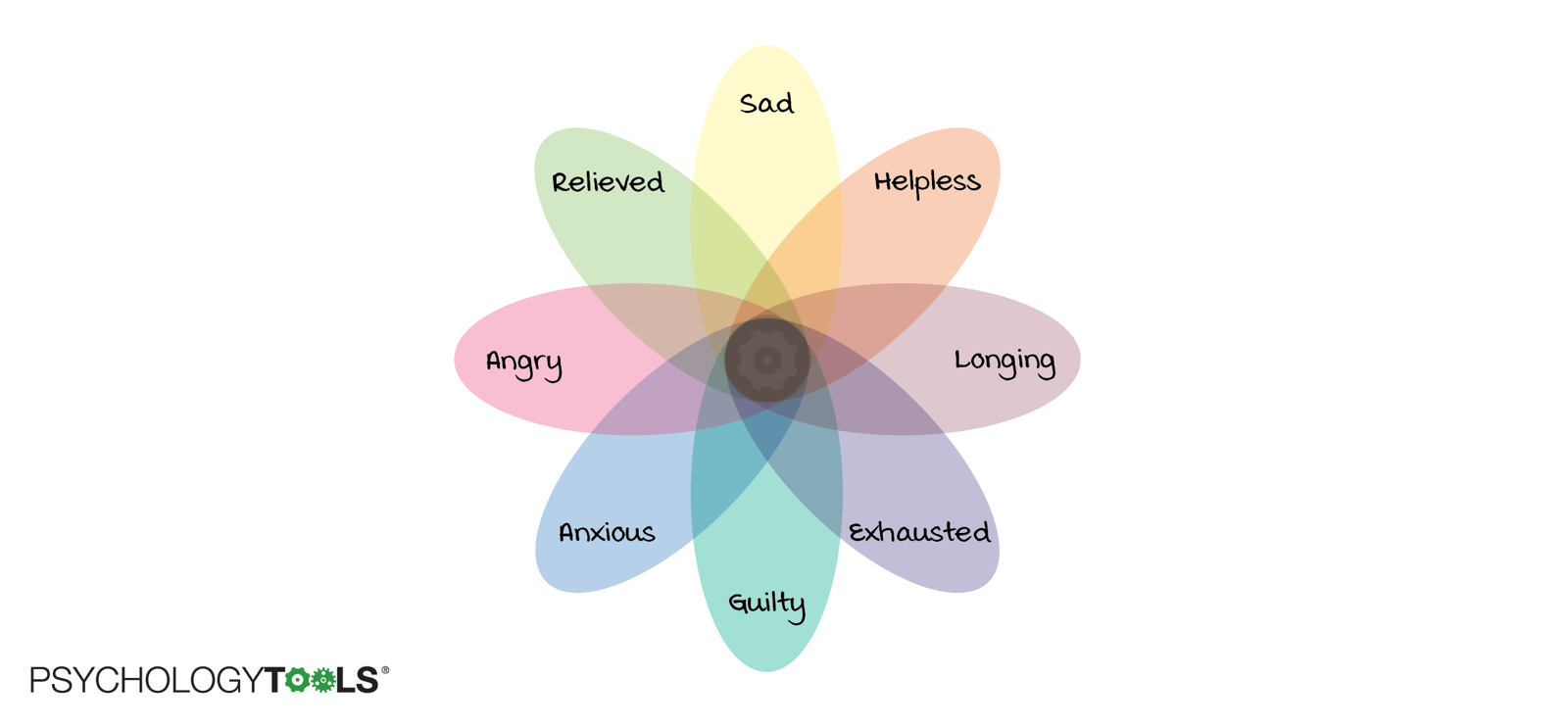

Grief is more than just sadness and you might be overwhelmed by a variety of different emotions and feelings in your body as your grief changes over time. Grief is different for everyone: everyone deals with it in their own unique way.

We can separate the effects of grief into thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. You might experience some, all, or none of these.

| How you might think and remember | How you might feel emotionally and in your body | How you might act |

|

|

|

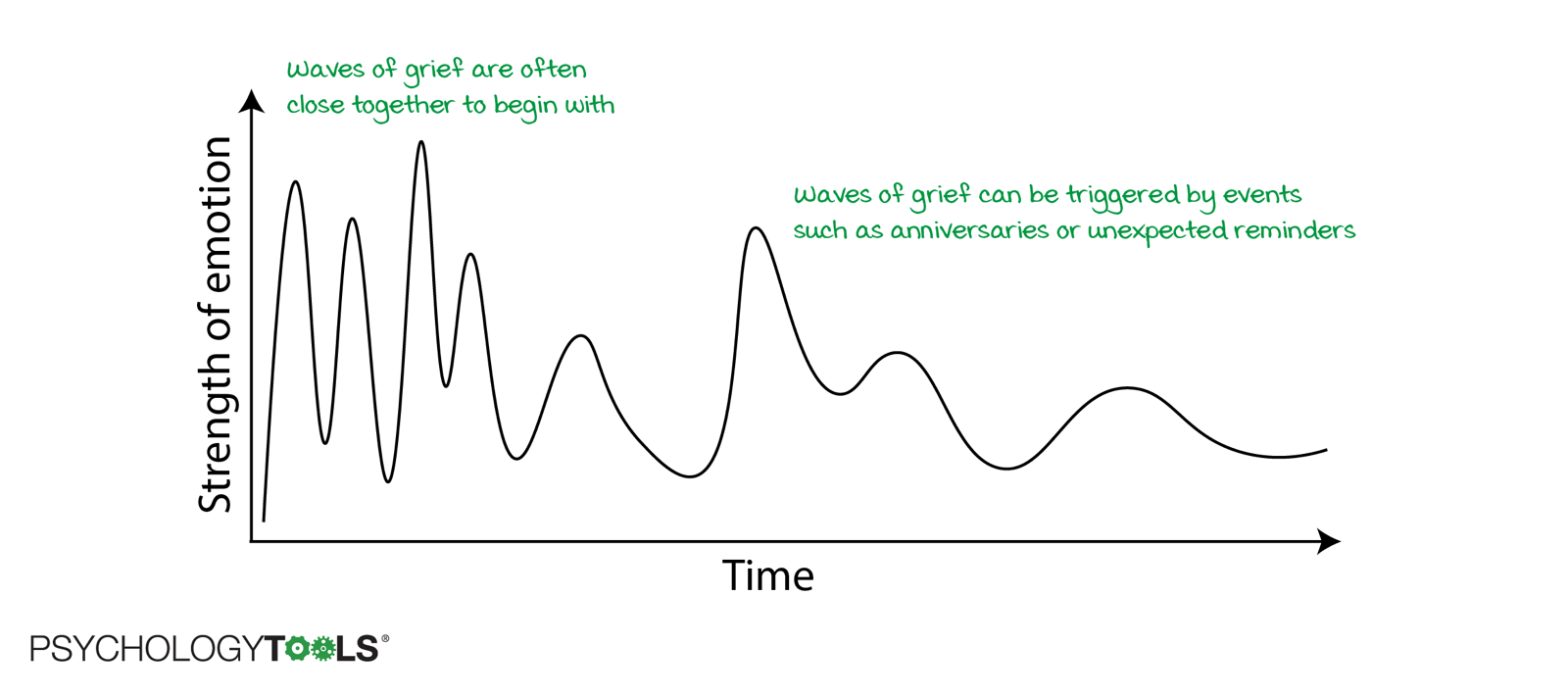

Grief often feels like it comes in waves that can initially feel intense and overwhelming. These waves of grief can feel like they come out of nowhere, or can be triggered when you are reminded of the person you lost. When you first lose someone, it can feel as though you are constantly being hit by enormous waves of grief – sometimes so close together that it feels as though you hardly come up for air between them. With time, the size of the waves tends to lessen, with larger gaps in between waves. As the weeks, months, and years pass by you will experience many ‘firsts’ as you navigate life without your loved one – your first dinner out, your first supermarket trip, your first birthday without them. In each of these moments it will be natural to feel their absence, and for waves of grief to be triggered again.

Figure: Grief often feels like it comes in ‘waves’. To begin with, the waves feel intense and frequent, but over time they tend to be spaced further apart and feel more manageable.

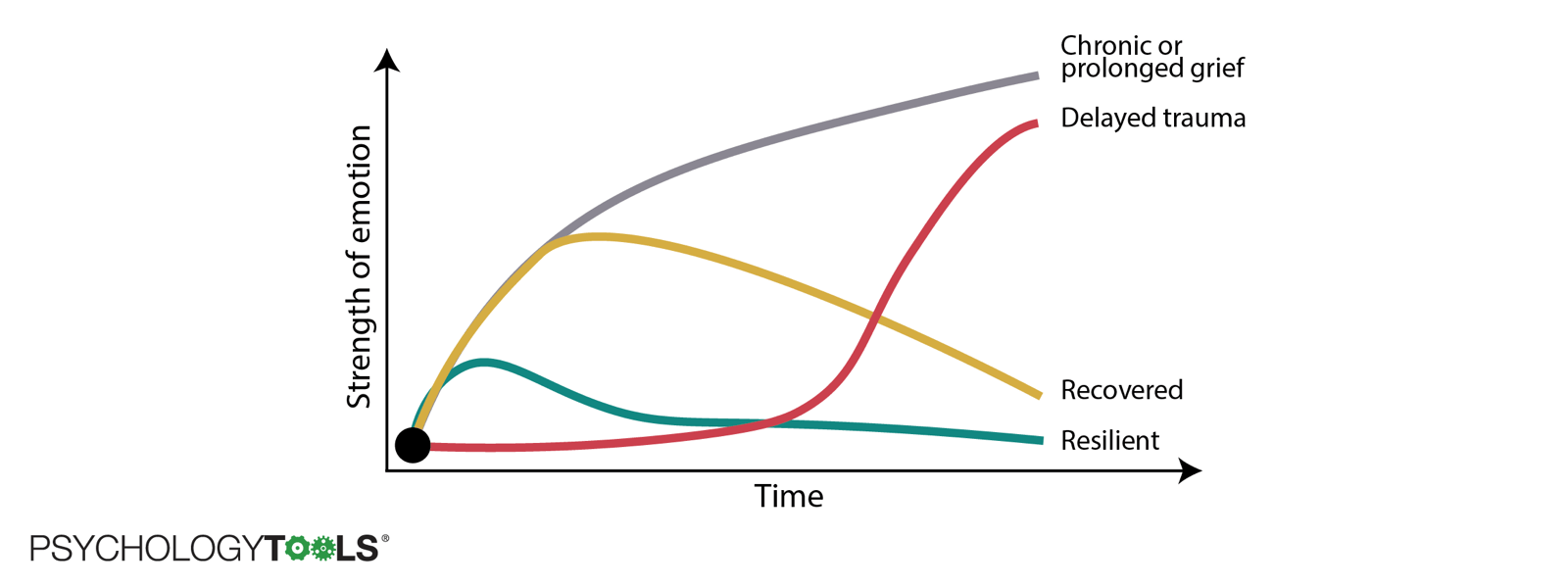

The difference between normal and complicated grief

There’s no ‘right way’ to grieve, and no ‘right amount’ of time to grieve for. However, some people’s grief seems to last for longer than others, follows a different course, and doesn’t seem to get better with time as we would expect. Psychiatrists sometimes call this ‘Prolonged Grief’ or ‘Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder’. The main difference from ‘normal’ grief is that the strong grief reactions continue at an unbearable intensity for much longer than would be expected, and impact the bereaved person’s life in powerful ways.

Figure: An illustration of different ‘trajectories’ of grief. The most common type is ‘resilient grief’. ‘Prolonged grief’ typically follows the rough trajectory of ‘chronic grief’. [1]

If you are struggling with a prolonged grief reaction you can feel as if you are in the depths of grief all the time, and can feel overwhelmed by an intense longing for the person you have lost. It can be a real struggle to carry on with your daily life and you might find you can’t get on with the things you used to do before, such as working, socializing and seeing friends and family. A prolonged grief reaction is more likely when the loss was particularly traumatic, for example after losing a child, or losing a loved one in sudden, violent or traumatic circumstances.

How other people might respond to your loss and your grief

It is natural for your friends and loved ones to want to be supportive. Sometimes though, you might find that the way that other people respond to you can be unhelpful. For instance, other people might:

- Feel uncomfortable and not know what to say.

- Find it difficult to talk about your loss with you and change the subject.

- Avoid you.

- Expect you to feel better and move on before you are ready.

- Not know how to respond in the way you need.

- Say things like “aren’t you over it yet?”.

- Want to talk about it too much with you.

- Shut you down, or try to cheer you up when actually you just want to talk about it.

Remember that it’s OK to let people know what you need and what you don’t. Grief can be like a rollercoaster: there will be times when you want to talk and other times when you don’t. Sometimes you might want a distraction and to not think about it, at other times all you might want to do is talk about how you feel. You may not know what you need from others and this can be confusing for you and them. Remember that there are no rules – whatever you’re feeling is OK.

Metaphors and models of grief

Psychologists have many different ways of thinking about grief. It used to be commonplace to think of grief as a process that goes through various stages. Some of these older models of grief were based on the idea that people ‘move on’ and ‘let go’ of their loved one. However, some people find this notion uncomfortable. More recent models of grief present alternative perspectives that you may find more helpful.

As you read the theories and models below, there may be some that resonate with your experience and others that don’t. That’s absolutely fine! Remember there is no right way to grieve – the theories are just some ways of understanding the process of grieving.

Loss is like a wound

When someone you love dies, it can feel as though you have been injured by their loss. Loss is often described as an open painful wound that needs healing. Just like a physical injury, the pain of loss is very raw to begin with. The wound is all that you can think about – it is all consuming – and any movement reminds you that it is there. In this early stage you may be so consumed by your injury that friends and family need to take extra care to look after you and be there for you.

Grief is often described as the process of healing from the wound. If the conditions are right then wounds will heal naturally in time.

Sometimes, though, it is too painful to acknowledge or tend to a wound – and so time does not always heal in the way we would hope. If a wound is left unattended then it can become infected, and the pain of grief worsens. An infected wound needs to be cared for in order it for it to heal. Talking about what happened, and how you feel is a way of tending to your grief and helping it to heal. It does not make the injury go away – a serious injury leaves a scar. However, as time and life goes on, it becomes a part of you, and no longer hurts in the same way.

Continuing bonds

Some ways of thinking about grief describe ‘stages’ that grieving people go through, often ending with ‘acceptance’ or ‘investment in a new life’. Grief researchers Denis Klass, Phyllis Silverman & Steven Nickman questioned these stage models, and proposed a different way of thinking about grief[2]. They argue that when a loved one dies you go through a process of adjustment and redefine your relationship with that person – your bond with them continues and endures. They say a relationship never ends – grief is not something that you go ‘through’ to ‘let go’ or ‘move on from’ your loved one. Instead, grieving is the process that helps you to form a different relationship with them.

Although your loved one has gone physically, you can learn to remember them, and they can continue to live on in your memories and heart. This will mean different things for each person, for example it could mean you continue to say goodnight to them and tell them about your day, you might carry on some of the routines and things that you did together, or you go to their favourite place on their birthday.

“they are remembered, not forgotten”

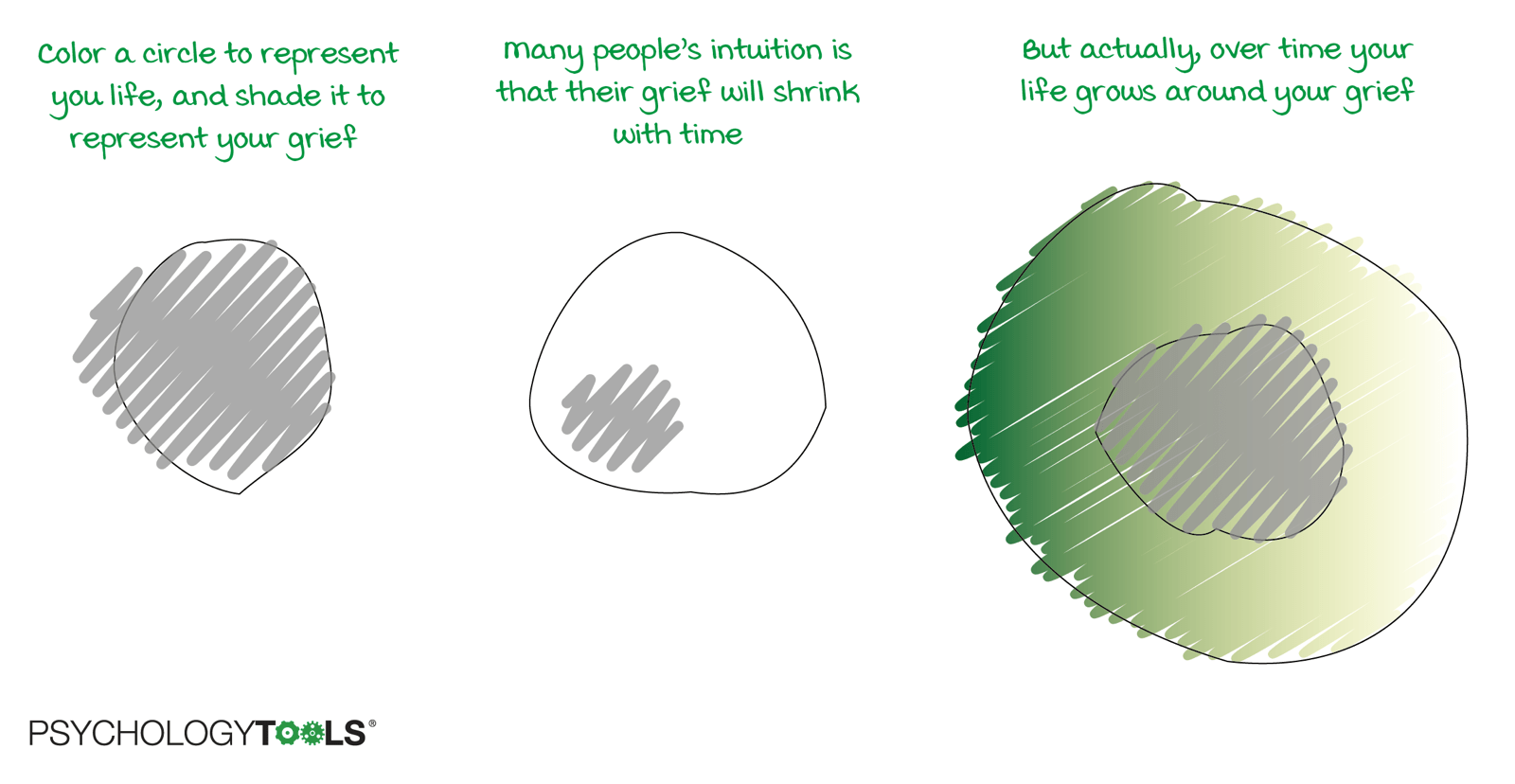

Life grows around grief

Another helpful metaphor for grief was developed by Dr Lois Tonkin. The idea is that we don’t ‘get over’ grief – it doesn’t ‘go away’. Instead as times goes on, you learn to grow around your grief.

Imagine drawing a circle on a piece of paper. The first one represents you and your life. Shade a section within that circle to represent your grief – soon after your loss it might almost be filling the entire circle of your life. Many people’s intuition is that with time the shaded section of the circle becomes smaller as the grief passes. Tonkin’s theory proposes the opposite – rather than the shaded area growing smaller, the outside circle (you and your life) grows bigger – your life grows around the grief. You will have many ‘firsts’, new experiences, and ups and downs in your life. You might start to reconnect with your family and friends, you may meet new people, start to socialize again and even start to have moments when you feel joyful and happy. As these experiences accumulate, the outer circle grows bigger. As this happens your grief remains but it no longer dominates and so becomes more bearable. In this way your life ‘grows around’ your grief, and you continue to carry your grief with you.

Tasks of grief

William Worden’s model of grief uses an acronym ‘TEAR’ to describe his four ‘tasks’ of grief [3].There is no order to Worden’s tasks, and grieving involves cycling between tasks over and over as you learn to come to terms with your loss.

- T = To accept the reality of the loss. Accepting the reality of the loss means accepting that your loved one has died. It is natural in the early days to want to deny what has happened, perhaps wanting to avoid the pain of grief. Sometimes it can be difficult to accept loss when your loved one died in tragic circumstances such as an accident or suicide. You may not want to think about how they died, which can get in the way of accepting the reality of their death. However, denial hinders grieving and in the long term can make you feel worse. Rituals and ceremonies when someone dies can help you to accept that the person you loved has physically gone.

- E = Experience the pain of the loss. This task involves working through the pain of grief. We live in a world where many of us have learned to supress or avoid difficult emotions. Others around you also want you to be OK, and so it can be difficult to find space to work through how you are feeling. However, avoiding our feelings does not make them go away, and can make the grief persist. The way we feel after a loss is different for everyone. There is no formula about which emotions you need to work through. Worden acknowledges that for each person grief is different. It is natural to feel any emotion like sadness, longing, anger, relief, despair, anxiety, numbness, guilt, shame or regret. Whatever you feel, it’s important to find ways to process and deal with your pain, however it affects you. This could mean talking about it with people you trust, or seeking counseling.

- A = Adjust to a new life without the lost person. Adjusting to life without your loved one will take time, and you may even feel guilty for doing so. This process will be different for everyone. It will also depend on the relationship you had and how much of your life you shared together. For example, losing a good friend who was a big support and confidant in your life will involve finding new ways of connecting with others and doing things that perhaps you used to do together. If you have lost your partner in life you may be figuring out how to do all the things your partner used to do. You may need to learn new skills and do things that you had never done before.

- R = Reinvest in the new reality. By ‘reinvesting in the new reality’ Worden means finding ways to continue an emotional connection with your loved one. This involves living your new life whilst also holding dear the memories of your loved one and allowing them to live on in your heart and memories. This will mean different things for each person. For many people it involves engaging with new connections and things in your life, that bring pleasure and meaning to your life again.

Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief

Many people have heard of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’s stage model of grief. This theory was popular in the 1960s and – for good or bad – has become a part of Western popular culture. What many people don’t realize is that Kubler-Ross originally developed her model while conducting therapy groups with terminally ill people: it was developed as a way to understand the stages of her patient’s own grief as they were dying. The model proposes that people go through five stages of grief which include denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

- Not wanting to face the reality of your loss. This may involve carrying on as if nothing has happened.

- Being angry about your loss, feeling that it is unfair and unjust. You may feel angry at others, or at your loved one for leaving you, or angry at yourself.

- Trying to figure out if there is anything you can do or change to make your loved one come back.

- Believing that there is no purpose and no meaning in life without your loved one. Feeling hopeless and depressed. Withdrawing from life and the people who care about you.

- Starting to come to terms with your loss. Beginning to feel that you will be able to live your life without your loved one.

An unfortunate aspect of the stage model is that it can set up an expectation that there is a ‘right’ way to grieve: a correct way to move through the stages. Actually, what we know is that grief affects people differently. A better way of thinking about the Kubler-Ross model is to understand that the stages are not linear: people don’t necessarily go through all the stages or in any particular order, and it is natural to move back and forth between stages over and over.

Treatments for grief

Psychological treatments for grief

If you feel that you are struggling to come to terms with your loss you may find it helpful to speak to someone about how you are feeling. Many people find bereavement counseling helpful, and you may be able to find a specialist bereavement counselor near you.

If you are struggling with symptoms of prolonged grief or traumatic bereavement, specific psychological interventions are recommended for these conditions.

Medical treatments for grief

Grief is a normal human experience for which there are no recommended medical treatments. Some medical professionals argue that symptoms of depression (which may perhaps predate or ‘sit alongside’ experiences of grief) can be distinguished from symptoms of grief and propose that medical treatments such as antidepressant medication can be helpful in these cases. This view is not without controversy.[4]

How can I help myself to grieve?

There are many things that you can do for yourself that will help you to work through your grief. We describe a selection of tasks and activities below that you might like to try. Some of the suggestions might make more sense at particular points of your grief journey, so don’t feel that you have to try all (or any!) of them right away. Some might be appropriate when your grief is raw, and others might be more helpful when you have had a little time to come to terms with what has happened.

Rituals & customs

Rituals help us to come to terms with loss and are a way to honor and respect our lost loved ones. They are so important that all cultures have their own rituals that are part of the grieving process, for example:

- Funerals are a ritual where we say goodbye, acknowledge the loss, or celebrate the life of the deceased.

- In cultures where the deceased are cremated, there is often a ceremony where the ashes are scattered at a place of rest.

- In some Indian cultures it is a tradition for the deceased’s family to be visited by family and friends to offer condolences and talk about how the person died.

- In many cultures there are rituals around preparing the deceased’s body, for example by washing the body.

- In western cultures a wake is usually held after the funeral.

- In Mexico there is an annual Day of the Dead to celebrate and honor the lives of the deceased.

From a psychological point of view, these rituals are imbued with meaning and fulfil two essential functions – they help us to make sense of what has happened, and confront the reality of the loss. You can make your own rituals to remember and celebrate the life of your loved one. For example, some people choose to plant a tree or hold a memorial service at their favourite place. You could think about what would be meaningful for you: how do you want to honor the life of your loved one? What would you like to do on anniversaries to remember your loved one?

“I don’t really go in for formal rituals, but I gave my son a name that would have been meaningful to my Dad. It makes me laugh to sometimes order his favourite pizza and think about how he used to be. These things are meaningful to me.”

Express your grief

Talking about your feelings of grief can help you to begin to come to terms with your loss. Could you find some close friends or family with whom you would feel comfortable talking about how you feel?

Another helpful way of expressing your grief is to keep a journal and write about how you are feeling. Some people find it helpful to speak to a professional grief counselor to express how they feel.

Remember that sometimes other people (understandably) want to make you feel better. Although this is well-intended, it could also mean that they try to cheer you up when actually you need to talk. If you want to talk, don’t be afraid to let others know that you don’t need them to make it better, you just need the space to be heard.

Make a memory box

After a loved one dies, some people find it important to keep their memories alive. One suggestion is to put together a ‘memory box’ of items and photos that remind you of your loved one. For example, you might include photos, some of their favourite belongings, their favourite music, a treasured item of clothing, letters, their favourite book, or sentimental items they gave you. You could place the box in a special place, and perhaps set a regular time when you visit your memory box like on their anniversary.

Telling your grief story

Talking about your loss and telling the story of your loss and grief can help to process what has happened. Whether you lost your loved one suddenly or after a long illness, there is often much to process and come to terms with.

As your mind tries to make sense of your loss, you may feel a need and even an urgency to tell your story and make sense of what has happened. This can be an important way of processing all the emotions that you are feeling.

If you don’t feel that you’ve had a proper chance to speak about what happened then you might find it helpful to write your story from your perspective, as if you are telling someone about what happened. If you decide that this is something you would like to try, here are some tips to get you started:

- What was happening in your life just before you found out about the death of your loved one? If they had an illness you might write about what was happening just before you received the news that they were going to die.

- If your loved one went through an illness, it might help to write about what that was like for you. You might write about the time you received the diagnosis, the medical interventions they went through, and your interactions with the medical staff. Try and notice how you were affected, reflect on your thoughts and feelings, and what it was like for you.

- Write about the moment you found out your loved one had died. How did they die? What happened? This moment is often very vivid, people often say they felt shock. What were you doing at the time? How did you feel? What did you do or think?

- How has your loss affected you? Reflect on your feelings, thoughts and how your grief is affecting your life.

Tackling avoidance

In the early days, the loss may be raw and it can be too painful to do things that remind you of your loved one. As time goes on, it is important to begin to face the places and situations that you have been avoiding. Here are some tips:

- Make a list of all the places, situations, people and tasks that you have been avoiding. For example, the swimming pool you used to go together, the takeaway you used to eat together, or certain people that remind you of them.

- Organize your list into a hierarchy, with the most difficult situations at the top.

- Make a plan for how and when you will start facing the situations you have been avoiding. Be kind to yourself, see if you can get a friend or close family member to come along with you to begin with.

- Pace yourself, you don’t have to jump in the deep end. It can be difficult to start facing reminders again, so be gentle with yourself and take your time.

- If you notice difficult emotions coming up, perhaps try the “Get in touch with the parts of your grief” exercise to help you work through your emotions.

Telling the story of your loved one’s life and your life together

Your loved one’s life wasn’t just about their death. It can help to remember your loved one’s life and the life you shared together. Writing from your perspective, imagine telling someone else about your loved one. Use the prompts below to get you started:

- What was your loved one like? What interests they did they have? What did they enjoy and dislike? What was their life like?

- What was your life together like? What did you enjoy together?

- Reflect on your memories. When you first met, how did your relationship developed and did you share any special moments?

- What were your hopes for the future with this person? How did you imagine that relationship being in times to come?

Write a letter to your loved one

Sometimes the feelings we have about our loved ones are not straightforward – while they were alive either of you may have said or done things that were hurtful, or which you regret. Writing to your loved one can be a helpful way of working through your feelings. Try to express how you feel, and say all the things you wish you had said. Here are some tips to get started:

- Firstly, there is nothing you cannot say: this is a personal letter and no-one else needs to see it. Let yourself write freely from your heart.

- You can tell your loved one the things you didn’t get a chance to say to them.

- You might tell them how you are getting on since they died; you can include the good and the bad.

- You can tell them how you remember and honor their memory.

- You can share the memories you cherish the most.

- You can share your regrets, or your feelings about any issues that were left unresolved.

- You can tell them about how you feel, you might want to include the different parts of yourself.

Once you’re done, think about what you want to do with your letter. You could keep it somewhere safe, or get rid of it if you prefer. There is no right or wrong answer, just be kind to yourself and do whatever feels right for you.

Get in touch with the parts of your grief

It is normal to struggle with different emotions when you are grieving: one minute you might feel angry and outraged, and the next minute ridden with guilt and regret. Psychologists encourage people to find ways to feel and ‘process’ their emotions: to acknowledge and work through your thoughts and feelings. Many of us are used to avoiding or suppressing how we feel, so it might feel quite strange and unfamiliar to face your emotions at first.

One way of working with your emotions is to imagine each emotion as one part of yourself. For example, there is one part of you that feels angry that your loved one has gone, another part that is sad, and perhaps another part of you that is scared.

Sometimes our emotions conflict with each other. For example, your angry part might be angry with the part of you that feels scared. Or the part of you that feels guilty might get in the way of the part of you that accepts what has happened. Here is an exercise to help you to work with these conflicts. In your own time, work through the steps below:

- First, name the different emotional parts of you. These might include the ‘angry part’, ‘scared part’, ‘depressed or sad part’, ‘guilty part’, ‘accepting part’, ‘relief part’, ‘in denial part’ … or any other parts you are aware of. Remember that no emotion is wrong, and that it’s OK to acknowledge how you feel.

- One at a time, bring each emotional part to mind one at a time and ask yourself some questions:

- What does this part of you think about your loss?

- How does this part feel?

- Where in your body is that feeling strongest?

- What does this part want to do?

- Now bring to mind a wise and compassionate part of you. This is the part of you that always has your best interests at heart, and which cares for you deeply. Imagine this part listening to all the other parts of you:

- What does this part of you want to say to the other parts?

- How can this part of you help the other parts to heal?

- What does this part of you want for you?

Dealing with regret and guilt

When someone whom we love dies it is common to feel some regret and guilt. You may recall things you did or said, or that you failed to do or say. Events that might ordinarily have seemed trivial may take on a new meaning in the light what has happened. Over time most people find ways of resolving these emotions. However sometimes guilt and regret can get stuck: as though it keeps looping on a circuit. This can be very distressing, and can get in the way of grieving in a healthy way. If you are feeling guilt or regret, here are some things that you might try:

- Write down your regrets.

- See if you can bring to mind a compassionate and warm outlook. We all have regrets and make mistakes, but that’s not the whole story of you and your loved one. See if you can take a wider perspective and offer yourself some kindness, like you would to a dear friend. Ask yourself:

- If your loved one could hear and see you regretting and feeling guilty, what would they say to you? How would they reassure and comfort you?

- What would a dear and wise friend say to you?

- If this was another person that was feeling regret and guilt, what would you say to them?

- Talk to your friends and family about how you are feeling, see if you can listen to their perspective, often they won’t be as harsh on you as you are to yourself.

Confronting difficult decisions

The death of a loved one may mean that you are faced with some challenging decisions. If you lived together you may have to confront financial decisions, or even have to move home. Even the smallest of decisions can feel overwhelming in the early days. If your circumstances allow, it is often advisable to postpone any big decisions until six to twelve months have passed.

If big decisions are unavoidable, you may need help to try to think through your options clearly. Consider enlisting the help of a trusted friend or family member to help you work out a plan. A classic problem-solving strategy is to:

- Write down what the problem is.

- Brainstorm the options that are available to you: what possible solutions are there?

- Consider the advantages and disadvantages of each solution, and weigh up which is the most helpful and wise decision for all concerned.

- Once you have a made a decision, plan what you need to carry out your chosen solution.

References

[1] Bonanno, G.A., Malgaroli, M. (2020). Trajectories of grief: Comparing symptoms from the DSM-5 and ICD-11 diagnoses. Depression and anxiety, 37(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22902

[2] Klass, D., Nickman, L.N., Silverman, P.R. (1996). Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief (Death Education, Aging and Health Care). New York: Routledge.

[3] Worden, J. W. (1991). Grief counselling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (2nd edition). London: Springer.

[4] Friedman, R. A. (2012). Grief, depression, and the DSM-5. The New England Journal of Medicine.

About this article

This article was written by Dr Matthew Whalley and Dr Hardeep Kaur, both clinical psychologists. It was reviewed by Dr Hardeep Kaur and Dr Matthew Whalley on 2020-08-04.